Roman Košťál - HIDDEN éditions

“The Seven Silents”

We are honored to present in HIDDEN Editions a unique and deeply personal series of paintings by Roman Košťál titled “The Seven Silents.” This collection was completed in the months following the death of his father, with each artwork exploring shadow plays of faded memories and the undercurrents of memory’s mycelial networks, touching upon themes of human loss and the search for universal meaning amidst painful life changes.

The title “The Seven Silents” refers to the silence left in the wake of his father’s passing, a silence of mourning itself. The number “7” alludes to the seven days in which God created the world, resting on the seventh, with death figuratively representing ultimate rest after life’s arduous journey. As Josef Čapek once reflected in his diaries, “To be dead is sweet, because more than sleep itself it is peace, solace, an end to pain and hardships; but this ultimate sweetness, the most that can be granted to a human being, the dead do not experience, do not feel.”

"This collection was completed in the months following the death of Roman’s father."

These paintings possess a transcendent, spiritual quality, reflecting the artist’s deep intuition and lyrical melancholy, which doesn’t dissolve into despair but rather celebrates the eternity of art in opposition to human life’s inevitable finitude. The black-and-white ghostly figures intermingle with scenes reminiscent of faded archival films, forming a dynamic collage of intense emotions and intimate nostalgia.

"The title “The Seven Silents” refers to the silence left in the wake of his father’s passing, a silence of mourning itself."

This series, created in the intimacy of the artist’s home rather than his studio at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, marks a departure from Roman’s previous work, making it both rare and surprising. It employs a new technique involving scalpel carving, where this aggressive material destruction paradoxically results in a sensitive and cohesive artistic expression. Compared to his earlier works, these pieces carry a metaphysical quality, with the glued canvas presenting a significantly softer drawing surface despite its rougher edges.

"This series, created in the intimacy of the artist’s home rather than his studio, marks a departure from Roman’s previous work, making it both rare and surprising."

Descriptions of the paintings

-

Description In the first painting, we encounter a modern-day apocalyptic Eve set against the backdrop of a burnt-out brothel that has transformed into a hell itself. A nude woman, posed with the femme fatale allure of Salome, dances with a lopsided back, but remains abandoned and in a Godot-like wait. The female figure embodies the grace of a Rodin sculpture in motion, the rawness of a lustful stripper, and the slyness of the demonic Lilith. Unfortunately, her dance partner never appears, leaving her in the grip of emptiness and solitude, crushing her like the edges of a hydraulic press. The red color evokes Mars, the planet of violence and rage, symbolizing the missing masculine principle – a memory of Roman’s late father, who will never return.text goes here

-

The second painting portrays an allegorical portrait of silence, as an addition to the previous series “Tilter,” composed of portraits of women without mouths (the word “Tilter” is the artist’s own invention, without any specific meaning). The girl in the painting, like the artist’s deceased father, can no longer speak. Her makeup dissolves in tears, showing a face that cannot smile but only weep. She lies on a bed, which might be a hospital bed or deathbed. Such ambiguity evokes a haunting uncertainty and a longing for more answers. This tragic scene echoes Hans Christian Andersen’s Little Mermaid, who, betrayed, threw herself into the waves, becoming silent sea foam. There is also a connection to Kafka’s Metamorphosis, where Gregor Samsa, transformed into a horrifying insect, loses his ability to communicate, although he passively understands human language. Roman’s painting shares Kafka’s typical absurdity and the inescapable nature of a hopeless fate.

-

The third piece captures a still, silent ghost with blurred lips, a scene halted in time – we feel as if we are viewing a frame of an old film reel. The scarf around the neck symbolizes breathlessness, while the football goal post on the bottom left resembles female genitalia, to which the man stares intently. The muscular hand resonates with exalted masculinity, contrasting with the gentleness of his gaze. Above his head floats an abstract symbol in the shape of “G,” an occult Masonic symbol. The letter “G” refers to “gnosis” (“knowledge” in Greek), but also alludes to the sexual “G-spot,” referencing Arthur Schopenhauer’s philosophical concept of “Wille zum Leben.” The footballer tilts his ear toward the viewer, waiting for a saving piece of advice, an escape rope from the stalemate he falls into like Icarus. Though one of Roman’s smallest formats, it remains the most voluminous in terms of its underlying material in this collection, as it is also the artist’s visual experiment.

-

The fourth painting, arguably the most charming in the series, shows a crystal-bright ghost of a bride. It is the very first painting Roman created after his father’s death. The composition lacks a groom, priest, or church interior – the deceased bride stands in posthumous darkness as everyone has vanished. The Reynekean softness and blurred contours create a subtle atmosphere of lucid dreaming. The blinding sparkle around the bride, like a shimmering cascade of electric sparks, suggests that in love, we see our partner as more beautiful than they truly are, just as a gem’s glitter is but an illusory reflection of light; once the light fades and the opium effect of amorous infatuation wears off, only the harsh truth remains, which the girl in the painting averts her gaze from.

-

The fifth in the series is a drawing of a broken crucifix, found abandoned among discarded waste. From the scene emanates Christ-like humility, surrender, and modesty, as the manneristically stretched, emaciated figure of the Crucified One gazes at his detached wooden feet, now pointed at his head. Both above and below, a blood-red background shines through, quoting the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, “That which is below is like that which is above, and that which is above is like that which is below.” The suffering and death of Christ and the subsequent acceptance of his departure from this world again refer to the passing of Roman’s father.

-

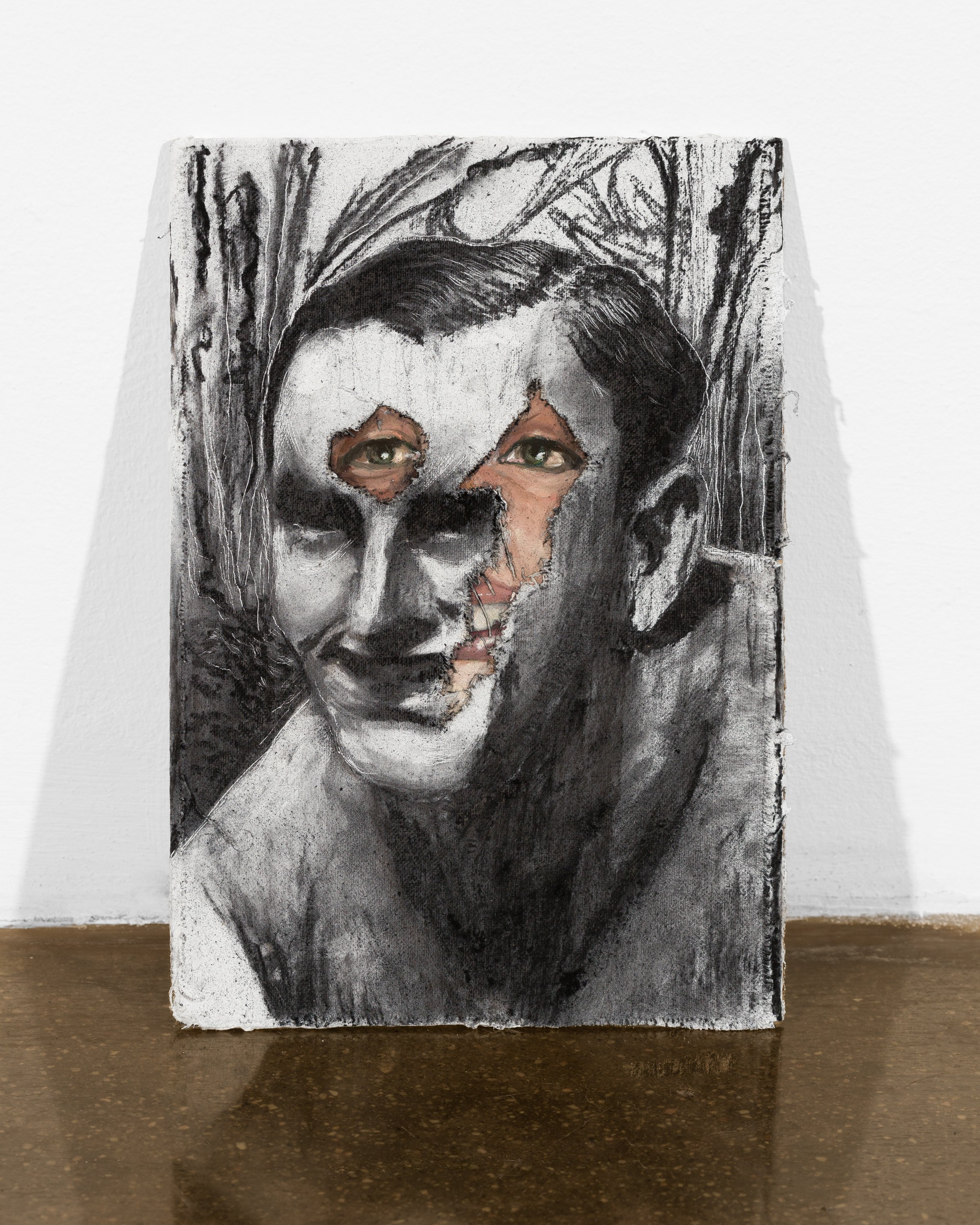

In the sixth painting, a phantom of an old-fashioned man appears, his features blending with the face of the painter’s former girlfriend, the only living person in the entire series, painted in color. The eye in a triangle references the all-seeing and judgmental eye of God. The dead continue to “live” within us through memories, but Roman has inverted this principle here, with a living person shining through the dead specter. The sharp features of the ghost contrast with the gentle features of the living girl – a corpse looks different from the living person, despite having the same body.

-

The final painting, etched with a scalpel, captures a weeping woman. Her left eye is entirely destroyed, as if someone had beaten her and struck her eye. Yet, the portrait leaves an impression of delicate beauty in the harmoniously shaped features of her face. The gentle light around her head forms a halo, resembling the corona of a solar eclipse. The chosen aesthetic draws inspiration from the Italian “giallo” film Suspiria. The fiery red background updates the old Gellner’s motto “After us comes the flood” to a new slogan “After us comes fire and scorched earth.” The element has changed – the destruction remains. This depicted girl is dead but remains poetically beautiful like Lenore. After all, it was E. A. Poe, who famously stated, “The death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.”