Lucie Hošková, despite her young age (born in 1999), is already an established artist with exhibition experience in Prague, Pardubice, and Kutná Hora. Her works, which blend an abstract informal aesthetic with specific mimetic scenes referencing Gnosticism and Neoplatonism, reveal a surprisingly intricate cosmology. The physis of matter in Hošková's work is conceived as a diabolical realm of suffering and decay, while its antithesis, the antiphysis of the metaphysical sphere of spirit, is depicted as a beautiful yet tragically unattainable goal, imprisoned within the human body (soma sema).

The artist has created her own myths (bearing some resemblance to the esoteric teachings of William Blake) with an overlay of Gnostic creationist doctrine, where the divine Pleroma, interacting with Sophia, gave rise to Chaos as the womb of the Demiurge, an intermediary between God and the material world. The two Trees of Knowledge of Adam and Eve, together with purely supersensory (noumenal) aeons, form the backdrop of the artist's philosophical tragedy. In this narrative, love is unmasked as primal desire (see Schopenhauer's Wille zum Leben), and the sole purpose of life is the liberation of the psyche, which can only occur after the terminal decomposition of the body. This body, encased in its sarcophagus of tendons and tissues, crushes our spiritual essence like a medieval iron maiden.

The painting titled Kyveta (Cuvette in Czech) serves as a laboratory tool for measuring the optical properties of solutions. Yet, it shares with the artwork a surreal atmosphere of de-objectification and depersonalized sterility, whether as a scientific aid or as a dispassionate act of procreation for the sake of producing offspring. The pregnant belly symbolizes a condensation of immanent tension—psychic as well as physical—comparable to the acute swelling of pus in a bursting blister. We are left uncertain whether Pandora’s box of the womb conceals a sacred infant or a feeble malformation akin to the grotesque creation in Lynch’s Eraserhead—and perhaps we would rather not know.

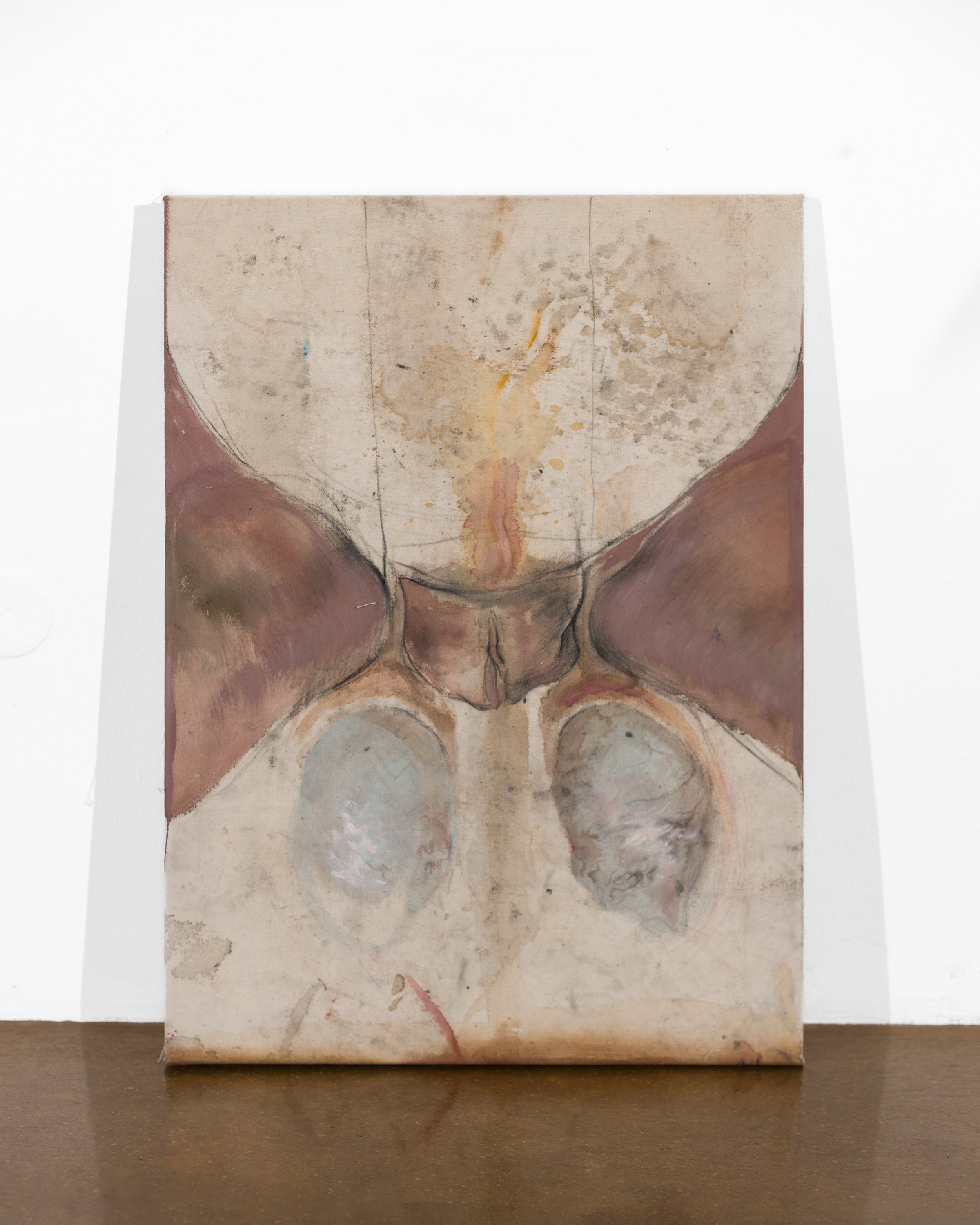

The pregnant abdomen traces the shape of a sphere, which, according to Plato's Timaeus, represents the ideal form. In contrast, the massive, amputated testicles juxtaposed with the exposed pubis represent the pulsating dichotomy of male and female principles in eternal motion, akin to the rotation of the north and south poles of magnets within a synchronous electric motor. The dissected testicles materialize the male fear of genital mutilation, whether self-inflicted (Origen) or by another (Uranus castrated by Cronus). This phobia was labeled "castration anxiety" by Sigmund Freud, describing a boy's fear of being castrated by his father as retribution for his incestuous desire to unite with his mother.

At the center of the image, within the intersection of two lines forming an "X," we see a prostituting vulva as an emblem of Schopenhauer’s Wille zum Leben, distorting reason. The artist conveys a shocking yet fatal truth: the world revolves around the axis of the female genitalia, which not only brings us into the world but, through blind, self-destructive lust, also leads us to the abyss of the grave. The composition of the image resembles the outline of an hourglass, evoking transience and impermanence, as reminded by the lyrics of Zeit by Rammstein: “We are heading toward our end, / without rest, just trudging forward. / Infinity awaits on the shore, / carried along by the river of time.”

Much like the treacherous antlion luring prey into its sandy trap, the depicted vagina dentata, hiding its shark-like teeth behind labial folds, waits to devour all our illusions of romantic love. Behind its hormonal makeup lies the grotesquely snarling, mating face of our own nature, disturbingly similar to Hlaváček’s drawing The Exile: “I conceived The Exile as an outcast from the sexual paradise. Behold, a terrible thirst for the former Edenic ‘purity.’ His sex has already transformed his mouth into a slimy female genitalia, convulsively open. [...] I executed the entire drawing in one breath, entirely realistically drawn—but then I was struck with such disgust and horror before my own work—that it had to come down.”

The scene also portrays the social tragedy within the nuclear family, where a woman, after pregnancy and childbirth, loses sexual interest in her husband, who, through enforced celibacy, is metaphorically castrated. The girl simultaneously becomes a mother—a mechanical factory for offspring—irretrievably losing her former allure, and with it, her dominance over libido-driven men (“Sex is about power,” as Oscar Wilde noted). By giving birth, the woman seems to lose a part of herself, nursing her child with her own blood as though it were a hematophagous parasite. Former romantic affection metastasizes into parental duty, and the partnership degrades into a pragmatic effort to maintain the family's operation. Thus, we circle back to the melancholic utilitarianism of the laboratory cuvette.

– Kamil Princ