AVU Diploma 2025

This summer’s AVU diploma projects offered a wide terrain: from fractured bodies and embroidered silence to baroque façades rewritten in concrete, from speculative archaeology to sculptural time machines. What links these selected works is not style, medium, or message — but presence.

Each piece here carries a specific tension. Some whisper, some pulse, some simply sit and wait. They come from places of care, from repetition, from inherited trauma or half-remembered myths. There are fragile membranes and heavy forms; mock monuments and soft gestures; myth-making and memory-shedding.

This selection is personal, instinctive, and unapologetically subjective. Not a competition, but a map of intensity.

Of the many rooms I walked through, these are the ones I kept thinking about after I left.

They deserve to be seen again, outside the time pressure of final critiques and white school walls. A quiet archive, built on presence rather than consensus.

Ondřej Navrátil

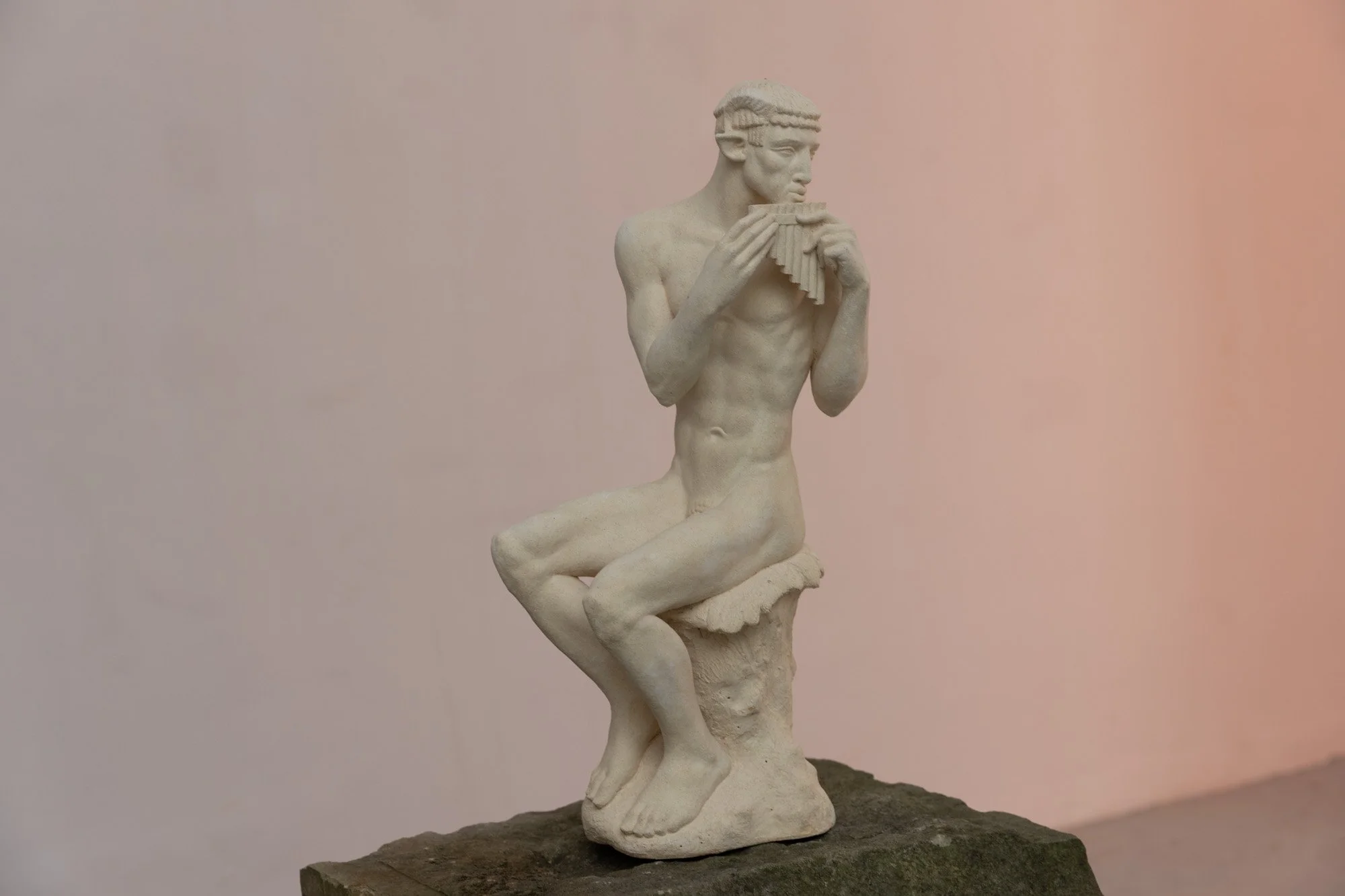

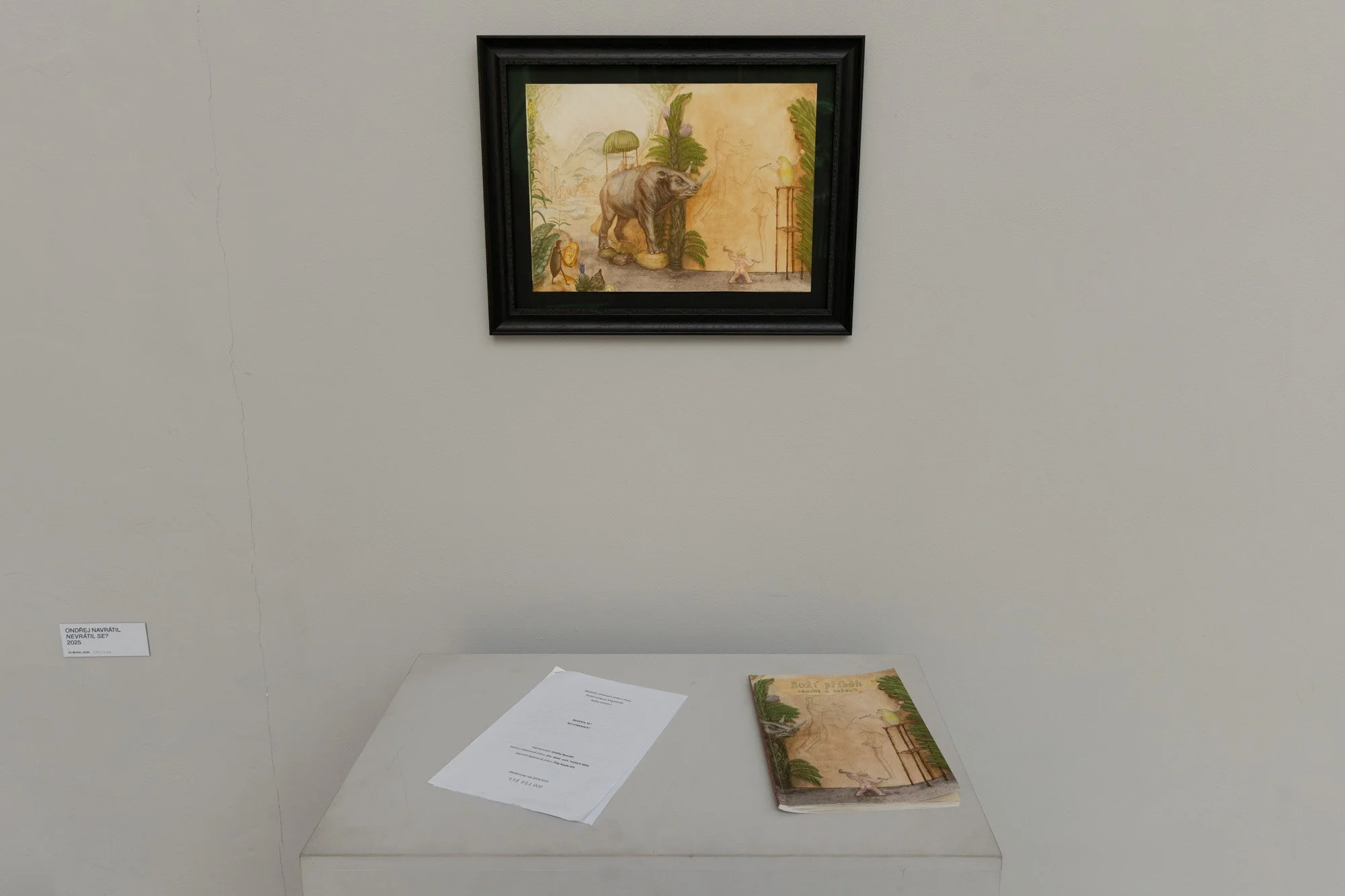

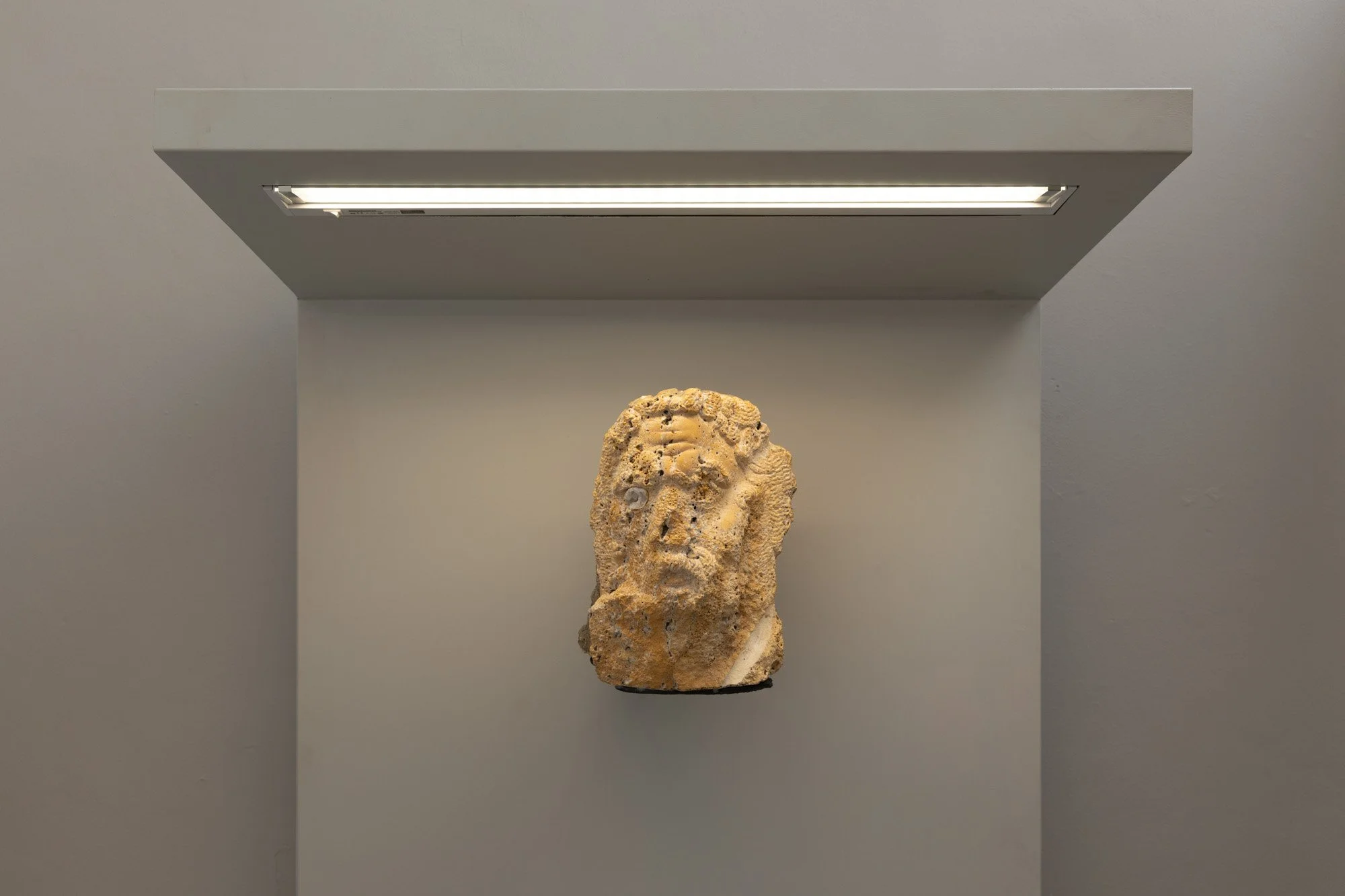

What happens when a diploma project turns into a time machine? Ondřej Navrátil constructs an elaborate narrative around a failed chrononaut whose GPS signal slipped through the centuries. The traveler’s message arrives in the present: cryptic coordinates, a short report, and a broken device. The artist sets out to investigate.

What follows feels like speculative fiction wrapped in museological drag. In a studio turned excavation site, we find staged relics: amber-preserved humanoid figures, sculptural fragments scattered like evidence, a massive stone head gazing blindly into the room. A photographtr shows Navrátil in goggles, emerging from a lake with a chunk of resin containing a full human silhouette. The caption treats it like a scientific discovery. The performance treats it like truth.

Anchoring the installation is the Transmutation Observatory, a metal pod on spindly legs described as a quantum engine, emergency hibernation chamber, or “just a time machine — once we find the missing battery.” Whether it actually works is irrelevant. The artist's tone balances between sincerity and satire: he insists it has nothing to do with gender, only with unstable timelines.

Throughout the podcast, Navrátil avoids offering clarity. The traveler, he suggests, might be real. He might be a friend. He might be himself. But maybe that’s beside the point. This isn’t a work about knowing, it’s about believing just enough. As he puts it, the installation is “kind of an ancient sci-fi,” where discovery and storytelling fold into each other like sediment.

The result is a self-authored mythology: half hoax, half prophecy. A world where time has warped, and what survives isn’t fact, but feeling.

Kateřina Štastná

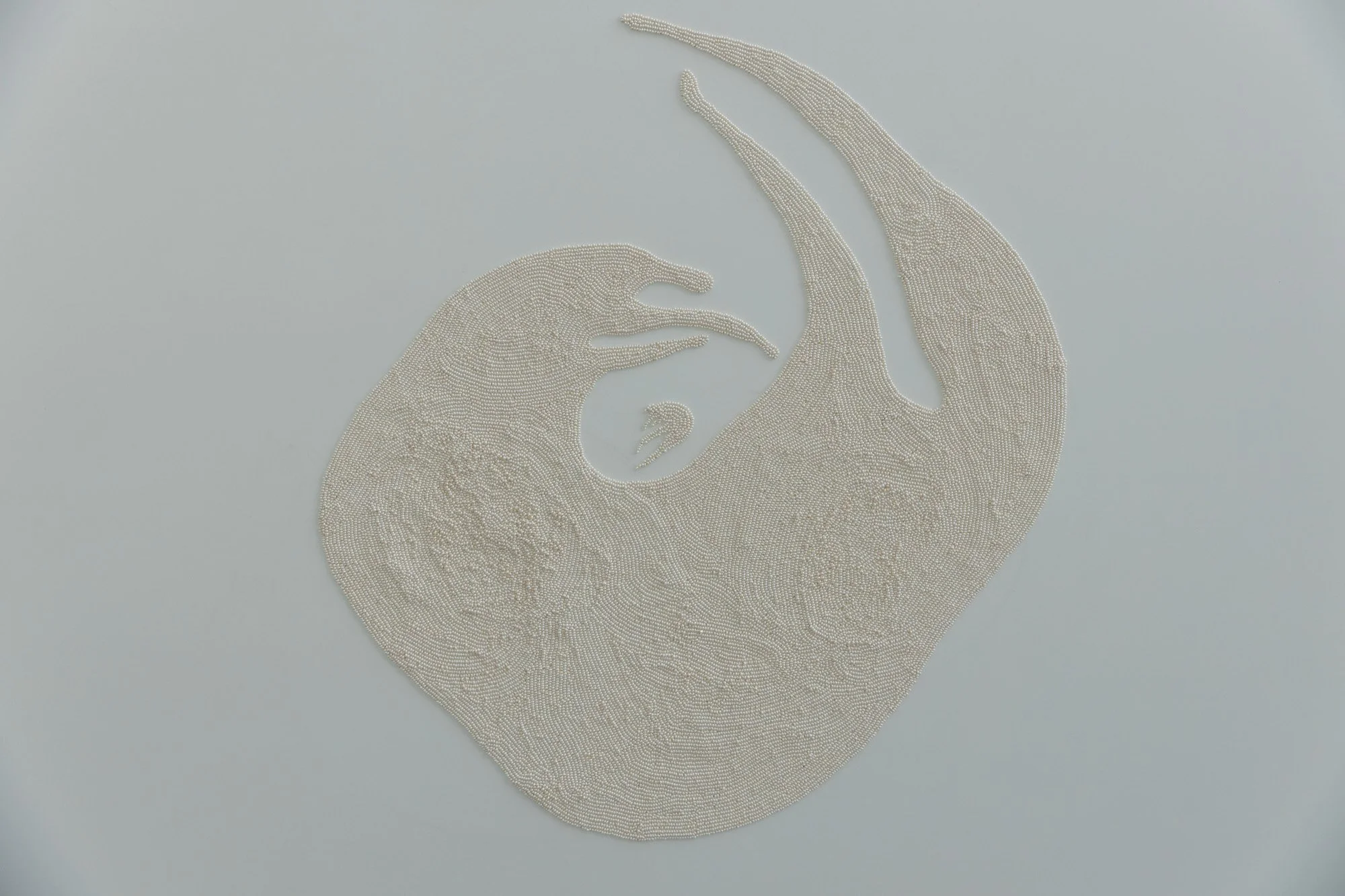

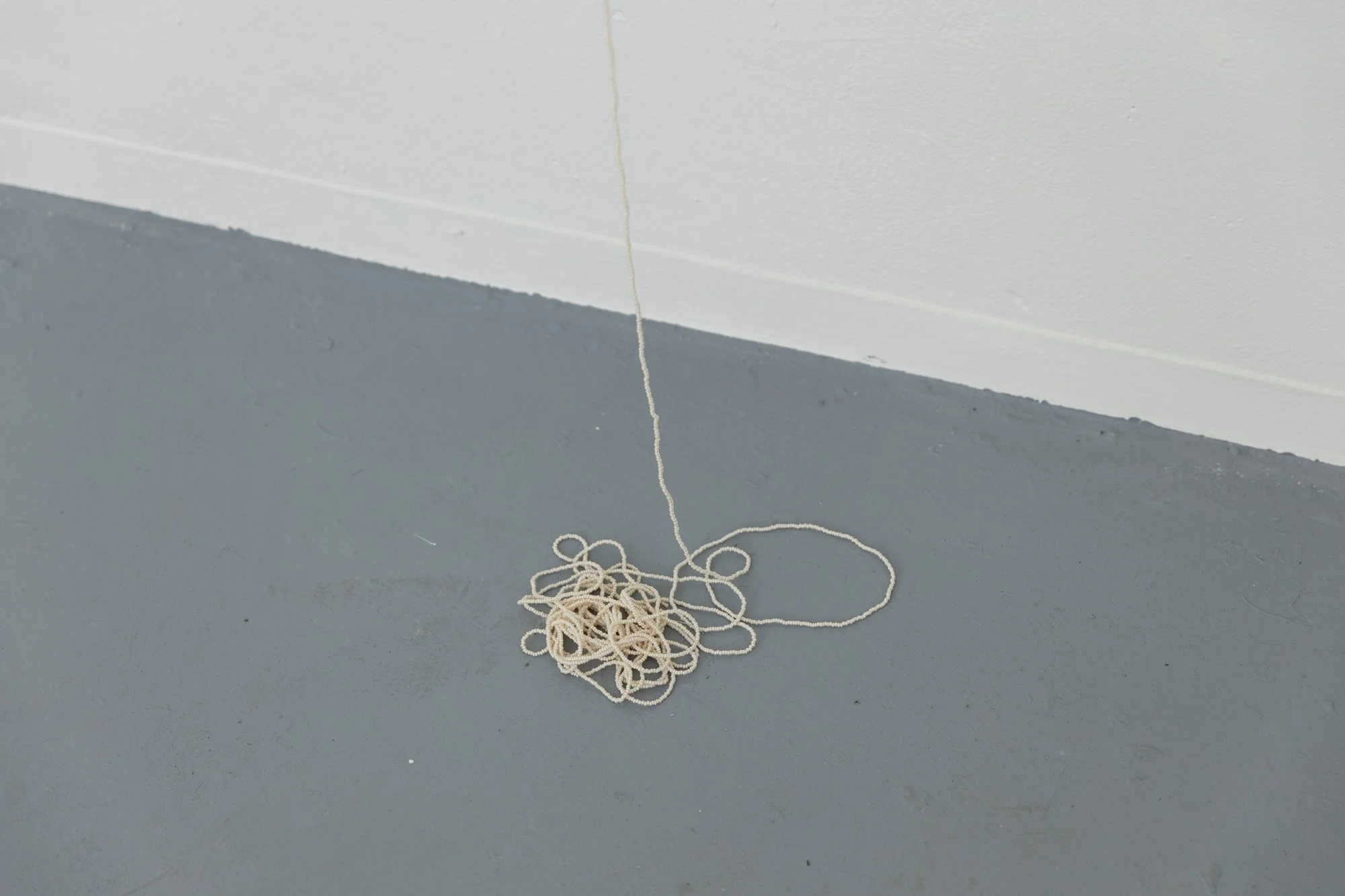

Two bodies stand close, leaning in. Their skin is smooth, pale, almost animal. Around them hang soft gestures, embroidered swirls, delicate abstractions, lines that seem to mimic breath or touch. One cocoon-like shape hovers nearby, somewhere between a seed and a shroud. A rope, loosely coiled on the floor, waits without tension.

Kateřina Šťastná’s installation moves with quiet gravity. Inspired by a personal relationship, it reflects on the subtle dynamics of presence, care, and transformation. Nothing here speaks loudly, but everything is felt, through shape, posture, and proximity. Her sculptures aren’t about bodies, they are bodies: searching, tender, unsure.

The embroideries arrived first, then the sculptures. But chronology doesn’t matter. What matters is contact, physical or emotional, real or imagined. Šťastná describes the work not as a statement, but as an atmosphere. It isn’t asking to be read. It’s asking to be felt.

This is not an installation about resolution. It’s about hovering in between — between people, between gestures, between becoming and being.

Podcast Soon

Darina Molatová

Three bodies lie across the floor. Each one is hollowed out, punctured by geometry, opened from within. The figures are soft yet weighty, fetal yet monumental. Some curl inward. Others are splayed, disassembled. All of them are marked by absence: pieces missing, cores exposed.

Darina Molatová’s sculptural installation explores the intersection of body and psyche, where the human form becomes both shield and site. The geometric voids in her works are not wounds but thresholds, spaces where memory intrudes, where trauma replays itself in the present. One figure folds around an invisible axis, as if protecting something that’s no longer there. Another is cracked wide open, its spine and skull removed, the most vulnerable part offered up.

These are not portraits. They are psychological states cast in silence. The posture of each form, crouched, resting, collapsing, evokes pain, but also potential. In their withdrawal, there is also a gesture of resistance. What bends does not always break.

As Van der Kolk writes, trauma lives in the body. Molatová gives it form, not to explain it, but to let it rest where it belongs: somewhere between remembering and rebuilding.

Julie Daňhelová & Štěpán kus

Although formally distinct, the diploma projects of Julie Daňhelová and Štěpán Kus share a quiet urgency in how they respond to place, not as something static or nostalgic, but as a fragile construction of labor, history, and visual codes. Both installations rework inherited forms: lace, relief, sgrafito, ornament. They don’t just quote them; they rewire them.

Placed side by side in the same space, their works unfold like an interrupted conversation. Daňhelová’s drawings and textile interventions trace forgotten hands and materials of the Ore Mountains. Kus’s concrete panels and urban motifs point to a more cynical present, where branding seeps into stone. Together, they remind us that every surface, mined, carved, stitched, or printed, contains a proposition for how we live and what we choose to see.

JULIE DAŇHELOVÁ

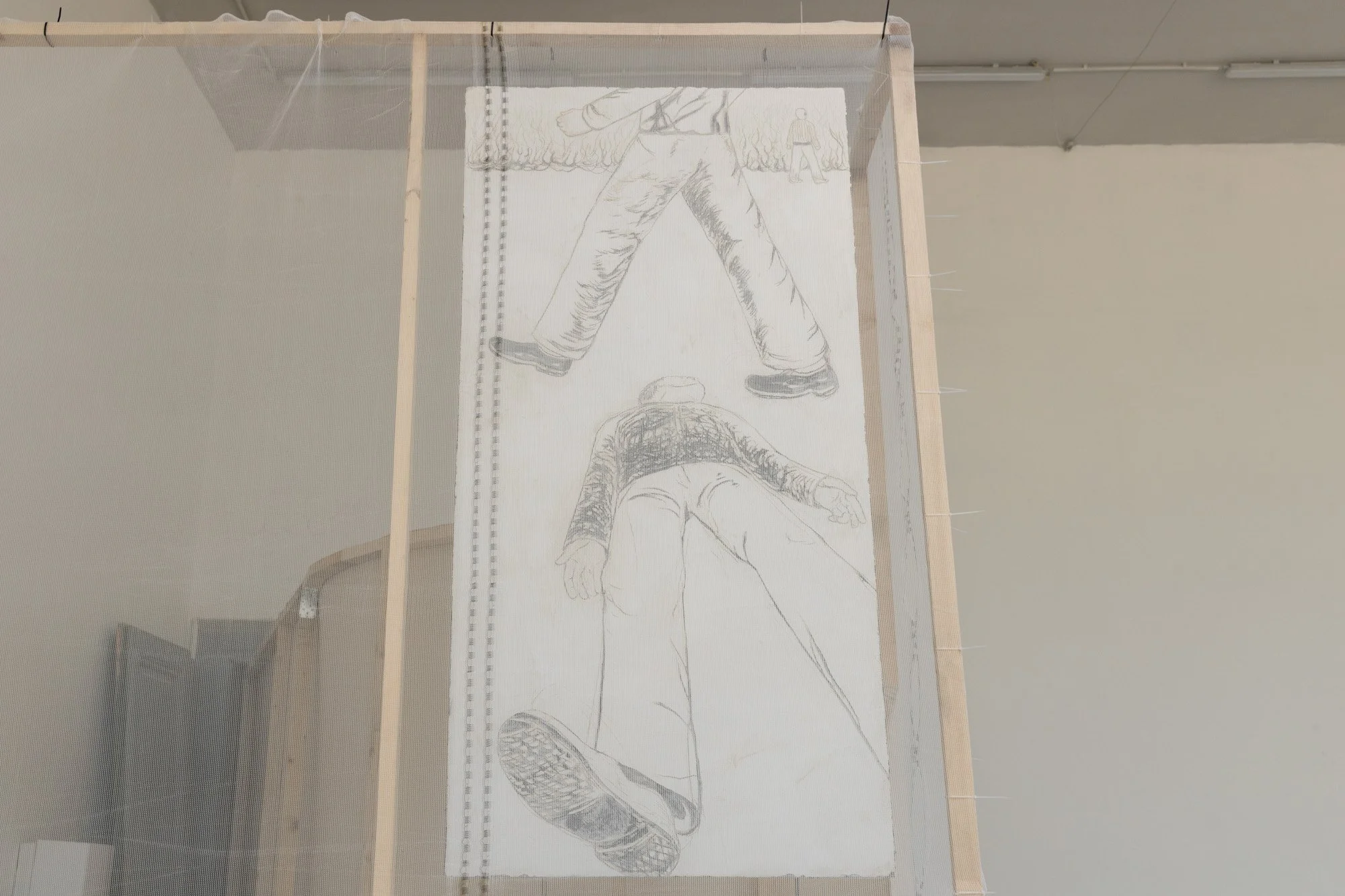

Julie Daňhelová’s diploma project is rooted in the Krušné hory (Ore Mountains), a region shaped by centuries of mining and delicate lace-making. Her drawings reimagine this dual legacy, heavy and hazardous labor underground, and the fragile, meticulous craft of bobbin lace created by miners’ wives and, later, by the miners themselves during winter months.

One large graphite drawing on handmade paper depicts historical tin washers, inspired by a Renaissance altar painting from the mining town of Annaberg. Another figure, ambiguous in gender and tender in posture, crushes ore with a hammer in a dimly lit shaft. Surrounding works capture abstract fragments of the Kraslice region a ruined mine tower, a peat bog, a copper furnace, or a schematic gnome.

The installation also includes dyed fabrics and a net-like construction made from antique bobbins and cotton threads, recalling both geological strata and woven history. Daňhelová collected these materials through fieldwork: rocks and ores from abandoned slag heaps, rusted tools from post-Sudeten landscapes, and cherry bark used to create natural pigment. Her work is both personal and territorial a soft monument to a place that continues to tremble with buried histories.

ŠTĚPÁN KUS

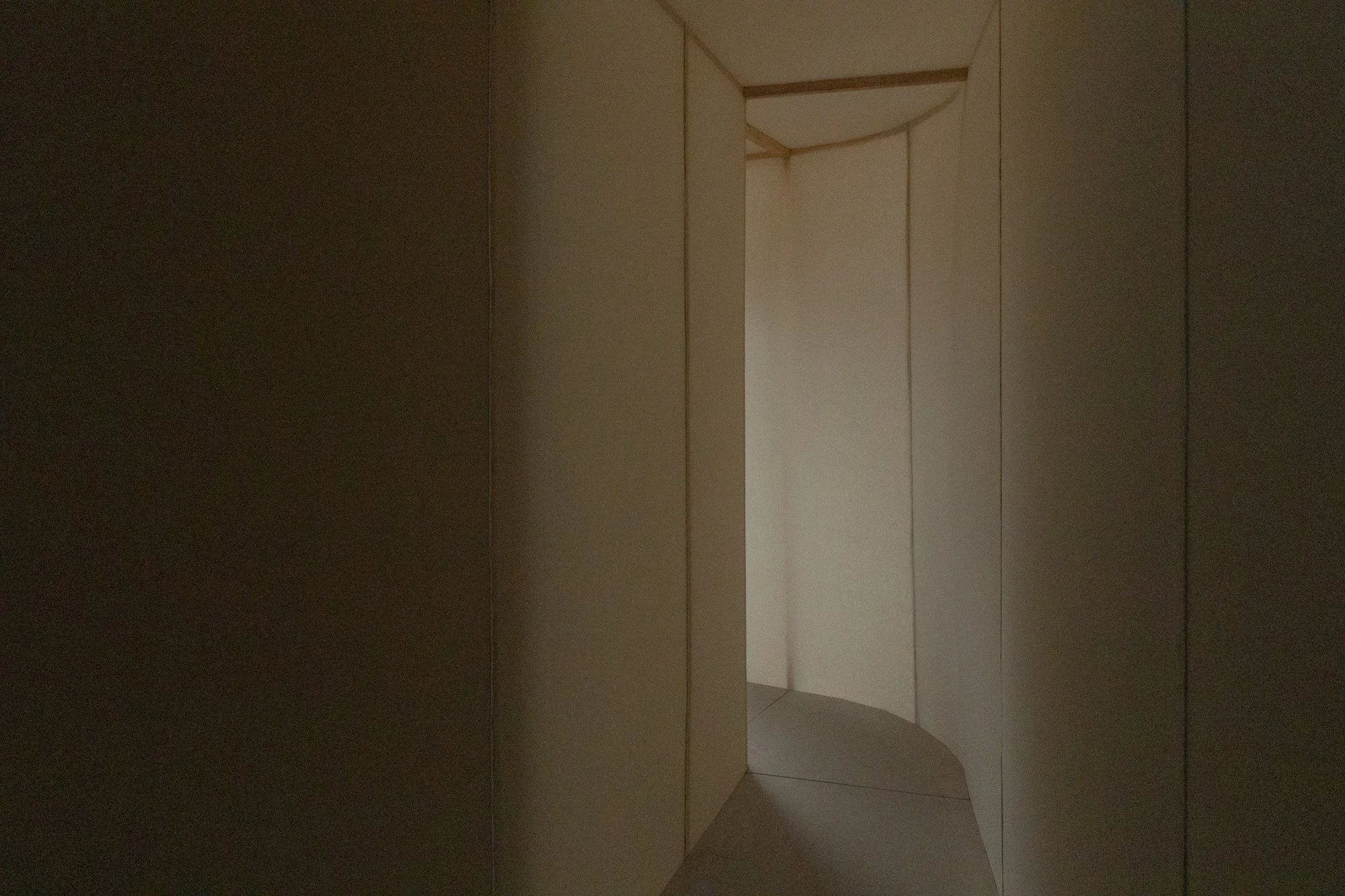

Štěpán Kus’s diploma installation maps the strange overlaps between historical architecture and commercial kitsch in today’s urban space. One concrete relief depicts a food delivery courier a contemporary worker cast in the visual language of socialist realism. The piece references classical labor monuments while questioning what labor looks like now, and who gets to be commemorated.

In a separate work, Kus recreates a fragment of a baroque façade, complete with stucco decor, interrupted by the bright logo of Captain Candy, a kitschy international chain known for its fake-pirate aesthetics. Cast in neutral concrete, the ad and the ornament collapse into the same visual plane, erasing distinctions between heritage and branding.

Elsewhere, Kus plays with sgrafito: one panel features a stylized “A” from the Czech e-shop Alza, rendered in the geometric logic of Renaissance decoration. These panels are mounted on a wooden tunnel-like structure covered in scaffolding mesh and fabric, which serves both as architectural intervention and metaphor a temporary portal into a cityscape in flux.

Ilona Koroman

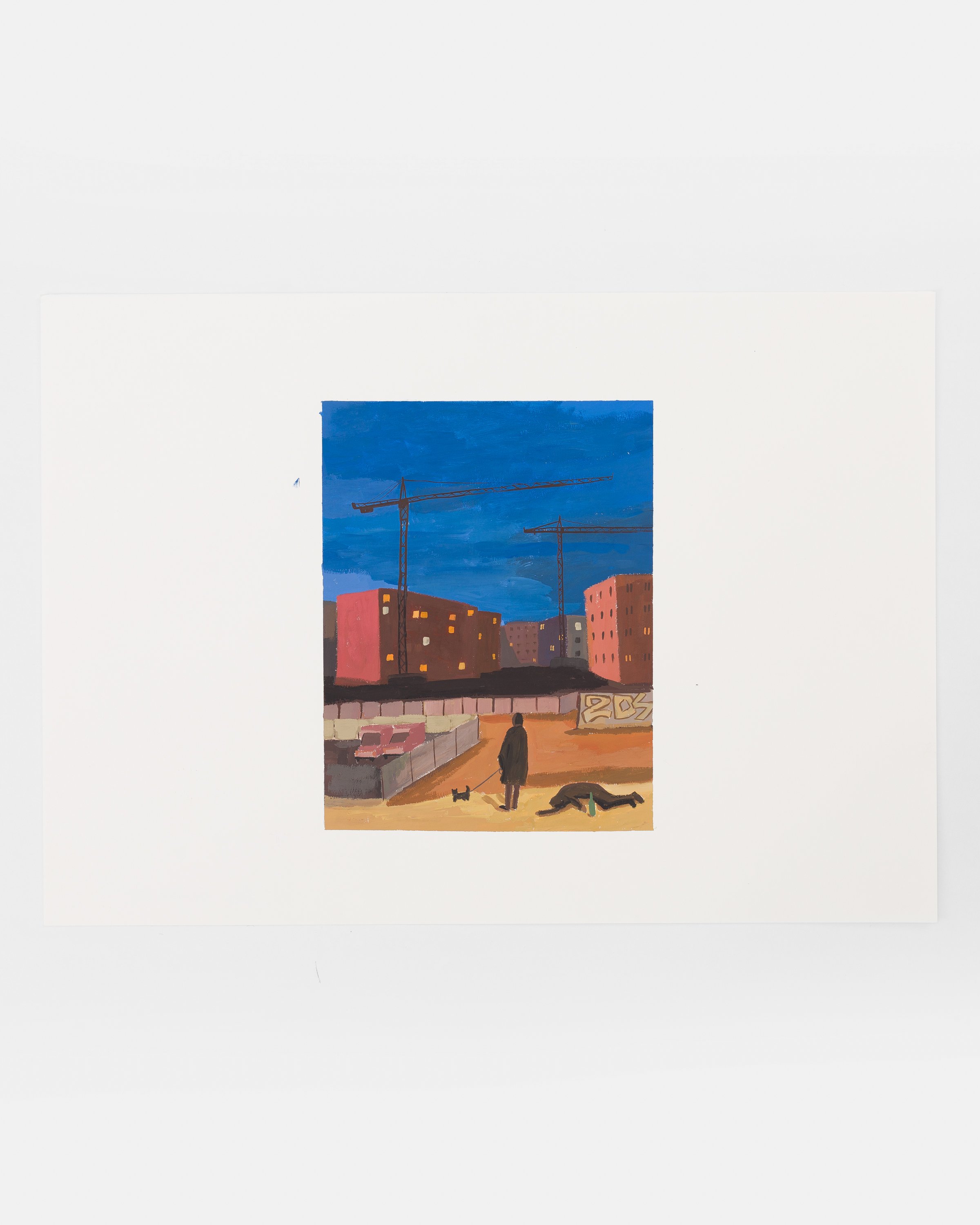

A man and a student stand in a hallway. Light spills from behind them, and a green door floats in the distance. It’s a real scene a corridor at the Academy of Fine Arts, but in Ilona Koroman’s painting, it feels more like a dream that remembers itself.

Her diploma installation is built from such moments: rooms within rooms, windows within paintings, time suspended between figures and furniture. Some canvases recall Prague interiors, others imagine cityscapes from memory or longing. A woman leans in a studio, a cat watches a bather, someone smokes beside a record player. None of it is spectacular. All of it is specific.

Koroman paints slowly. Her process, she says, is layered and open-ended, often picking up threads from earlier works, letting stories unfold without rush. The figures aren’t portraits. They’re presences. Carriers of mood, distance, and soft tension.

The result is not just a collection of paintings, but a network of rooms, quiet, connected, filled with things unsaid.

Podcast Soon

Mária Jančová

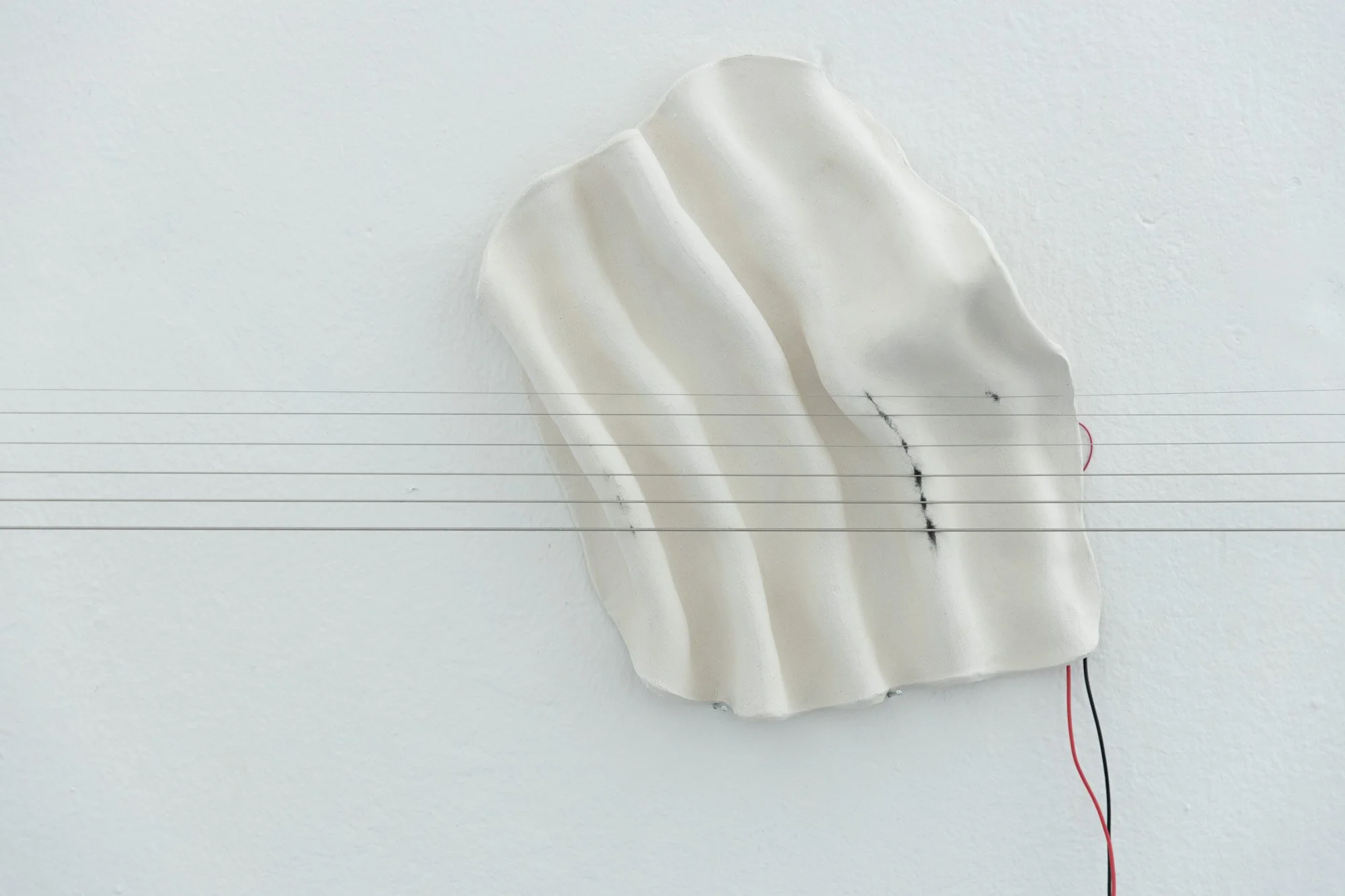

In Polyphony of Absence, Mária Jančová offers a fragile orchestration of materials on the verge of silence. Ceramic vessels, plaster membranes, powdered traces and taut strings form a space where touch becomes vibration and memory becomes sound. The work doesn’t scream, it resonates.

Rather than a fixed installation, Jančová’s piece behaves like a breathing system. Activated by presence, it responds to human and non-human gestures alike: footsteps, wind, a cricket’s chirp. Her DIY resonators and tactile sound-objects invite play, yet remain haunted by ephemerality.

Absence, here, is not a void, it is a field of tension. It accumulates, hums, lingers. The work functions as an archive of impermanence, of gestures barely completed, of words never spoken. Time is sensed not in minutes, but in dust. In this shared resonance chamber, Jančová conjures a poetics of almosts.

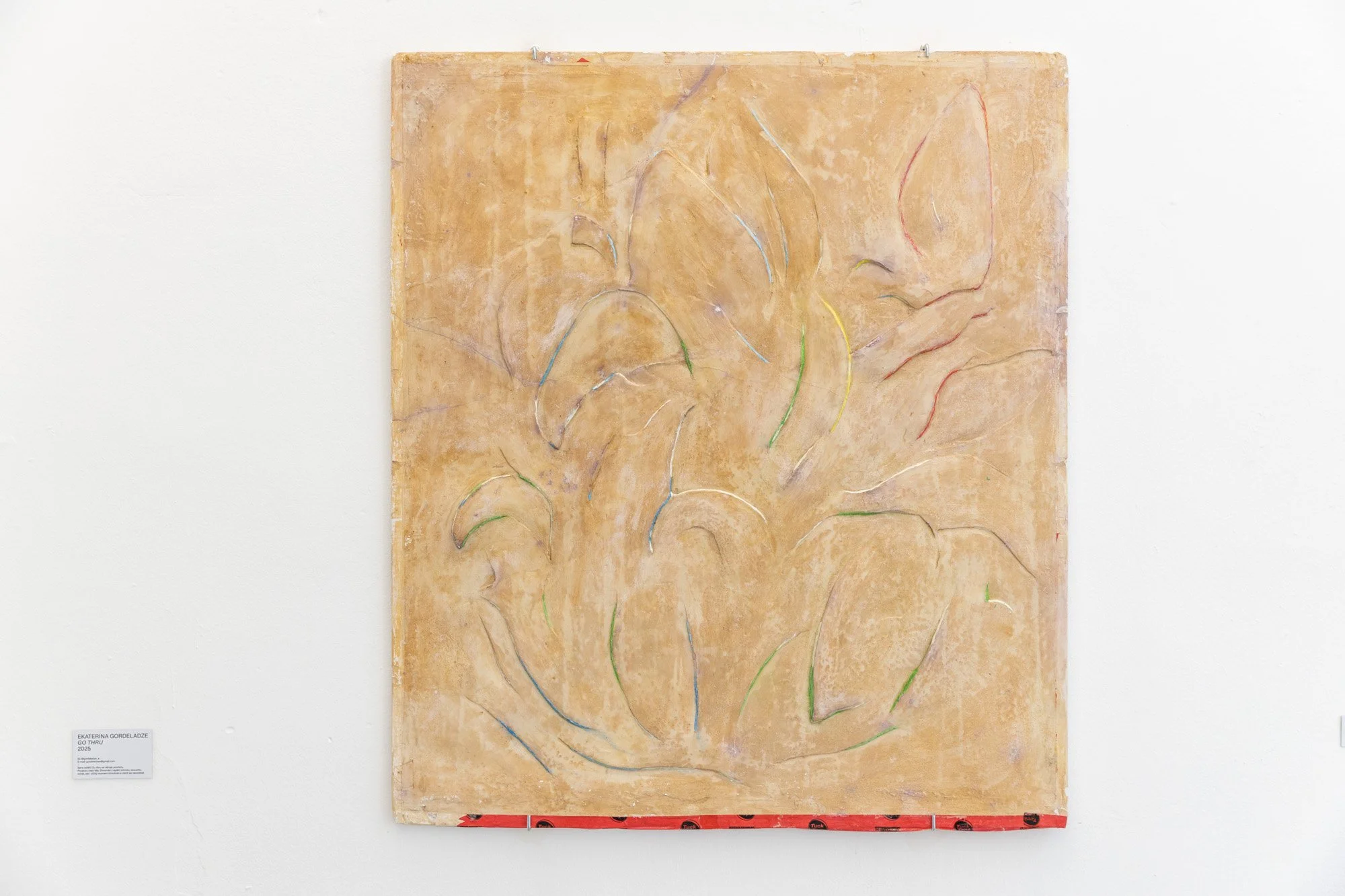

Ekaterina Gordeladze

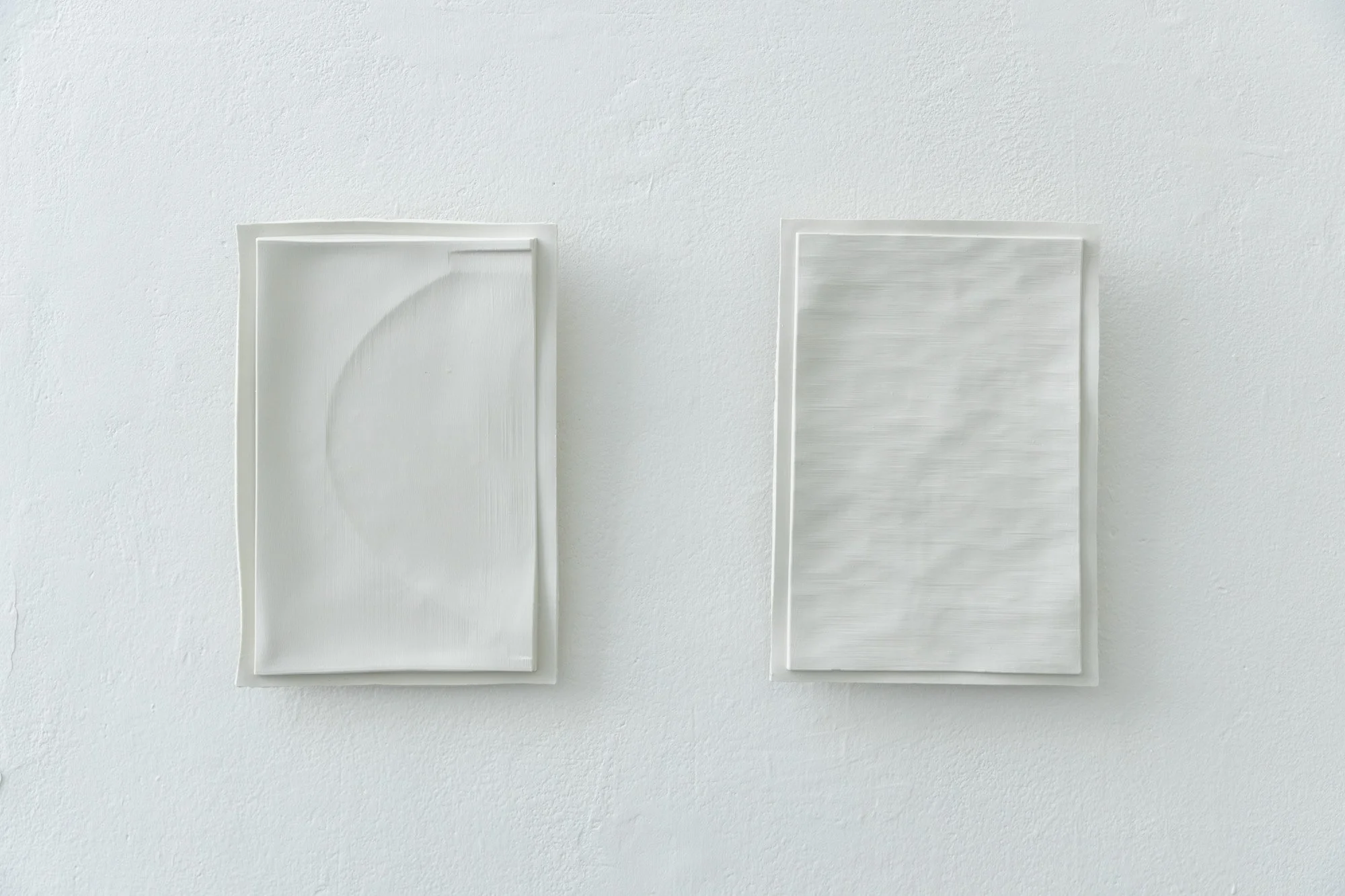

A shoulder presses into the wall. A torso folds in on itself. These are not paintings in the traditional sense, they are sculptural reliefs, fragile membranes where bodies emerge not in illusion, but through pressure, contact, resistance.

Ekaterina Gordelanze doesn’t depict the figure. She carves it, layers it, protects it. Working within a sculpture studio, her pieces stand at the threshold between object and image, not quite sculptures, not quite paintings, but something in between. Each surface is worked by hand, with gestures that feel more like care than construction.

In the podcast, she described the process as “showing something, while still holding part of it back.” Her forms are deliberately partial, glimpses of backs, thighs, or hips, never fully offered, never entirely absent. They resist being read, yet ask to be felt.

Some marks are rubbed away. Others sink beneath the material. Time, memory, and skin are compressed into each relief, until what remains is not a figure, but a sensation.

These works are not statements. They are thresholds. You don’t interpret them. You stand before them, and recognize something that has no name.

Podcast Soon

Jolana Škachová

…Even if it were your own hand, you wouldn’t like it if it touched you…,

Jolana Škachová paints the everyday not as we see it, but as we almost feel it, before thought hardens into words. A tea towel clings to a hook like a memory with no context. A curtain lifts slightly, and that breath of movement becomes the entire story.

Her works unfold like overheard whispers, partial, intimate, and emotionally charged. The title, lifted from a fleeting moment in Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, anchors her practice in the fragile terrain between presence and retreat. Through drawings and paintings, Škachová captures the suspended poetics of domestic space, mapping moments we live beside but rarely name: absence with texture, silence with weight, contact without touch.

This is tenderness under a microscope. And beneath the surface, a quiet kind of defiance.

Minh Thang Pham

Minh Thang Pham’s diploma painting is the result of a five-year journey through identity, memory, and the Vietnamese diaspora. After years of performance-based work focused on family, language, and intergenerational healing, Pham turned toward painting, slowly layering one single canvas over the course of four years, using brushes, sponges, and eventually Vietnamese lacquer.

The shimmering yellow surface is not just pigment, but the result of dozens of transparent lacquer layers, polished by hand in the humidity-dependent rhythm of the Vietnamese climate. During a residency in Huế, Pham studied traditional lacquer techniques under Đỗ Kỳ Huy, working with natural resins, eggshells, mother-of-pearl, and local minerals. The process is meditative, tactile, and rooted in climate, history, and care.

Next to the monumental canvas, Pham presents four small lacquer works, quiet and intimate objects that fit in the hand, offering a moment of stillness. Together, the works speak of return: to heritage, to fragility, to things that take time.

Martin Kolář

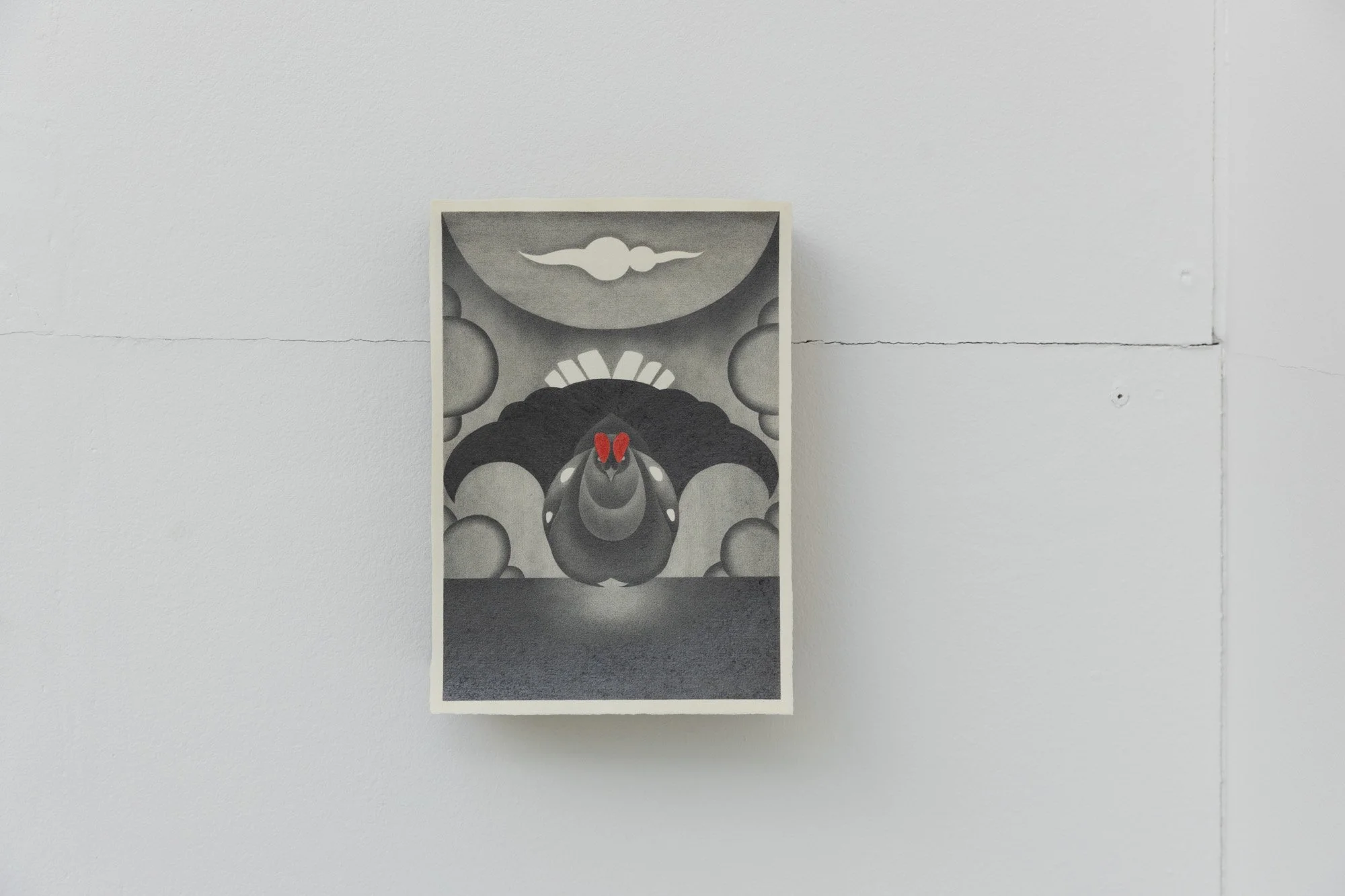

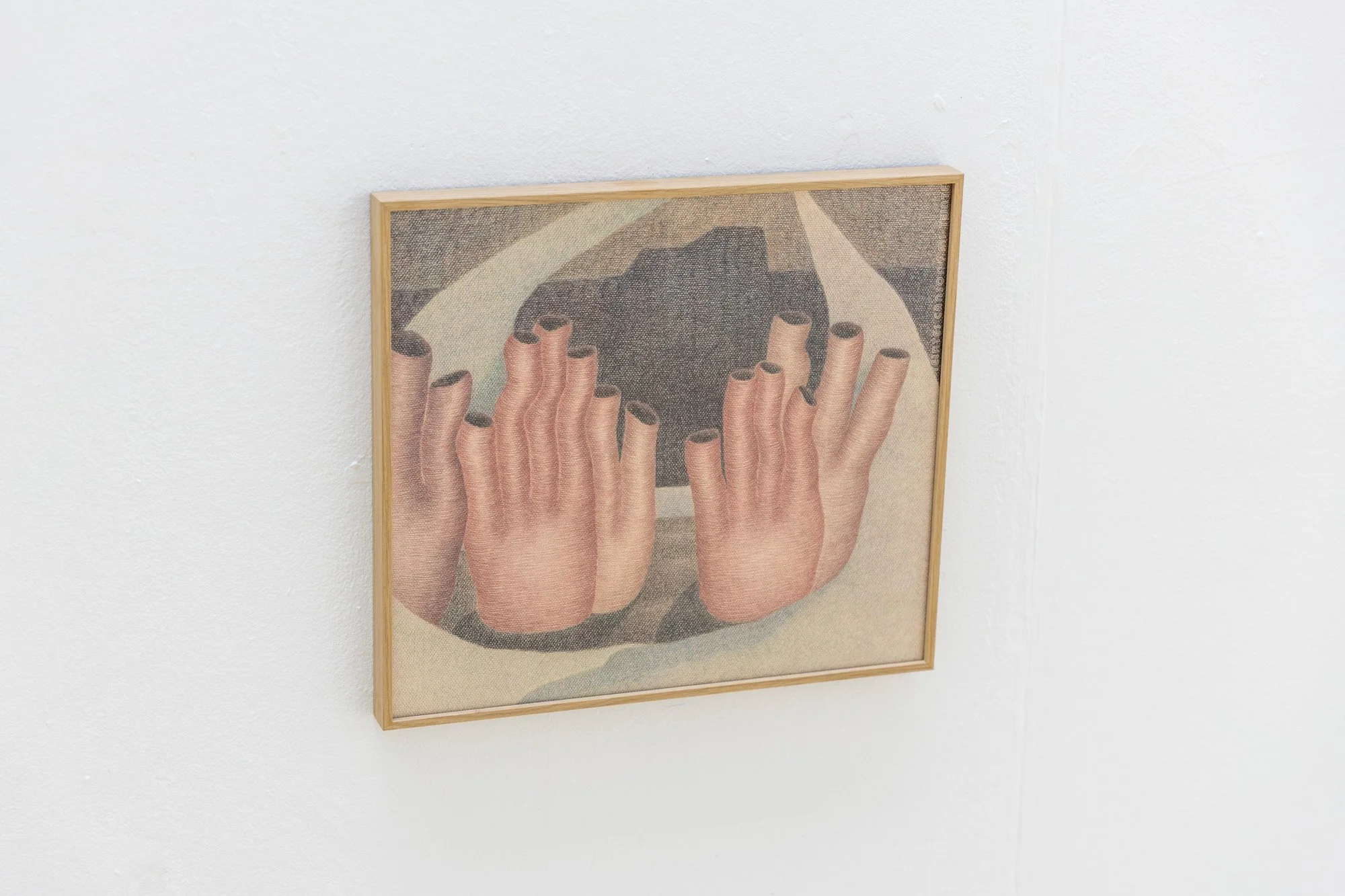

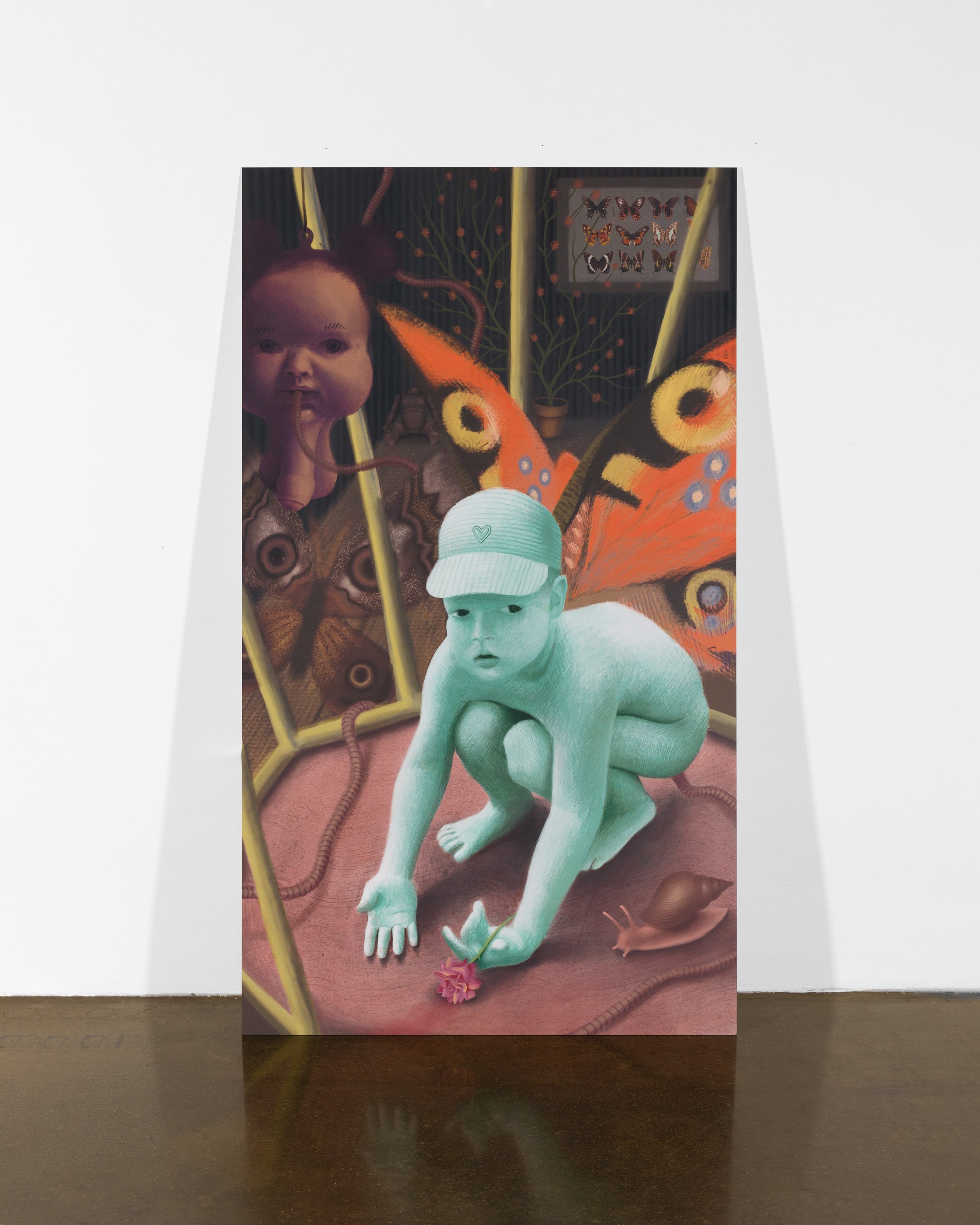

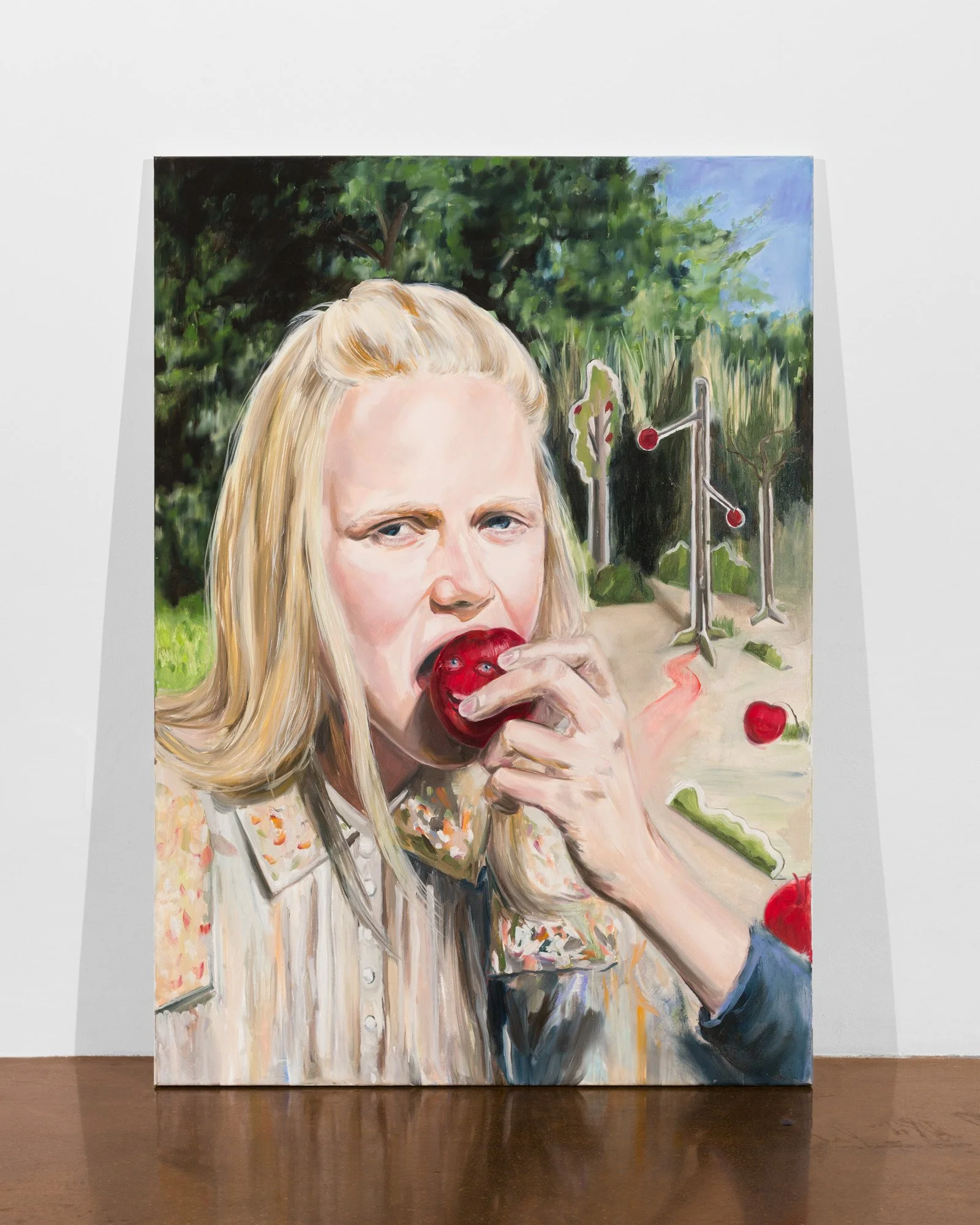

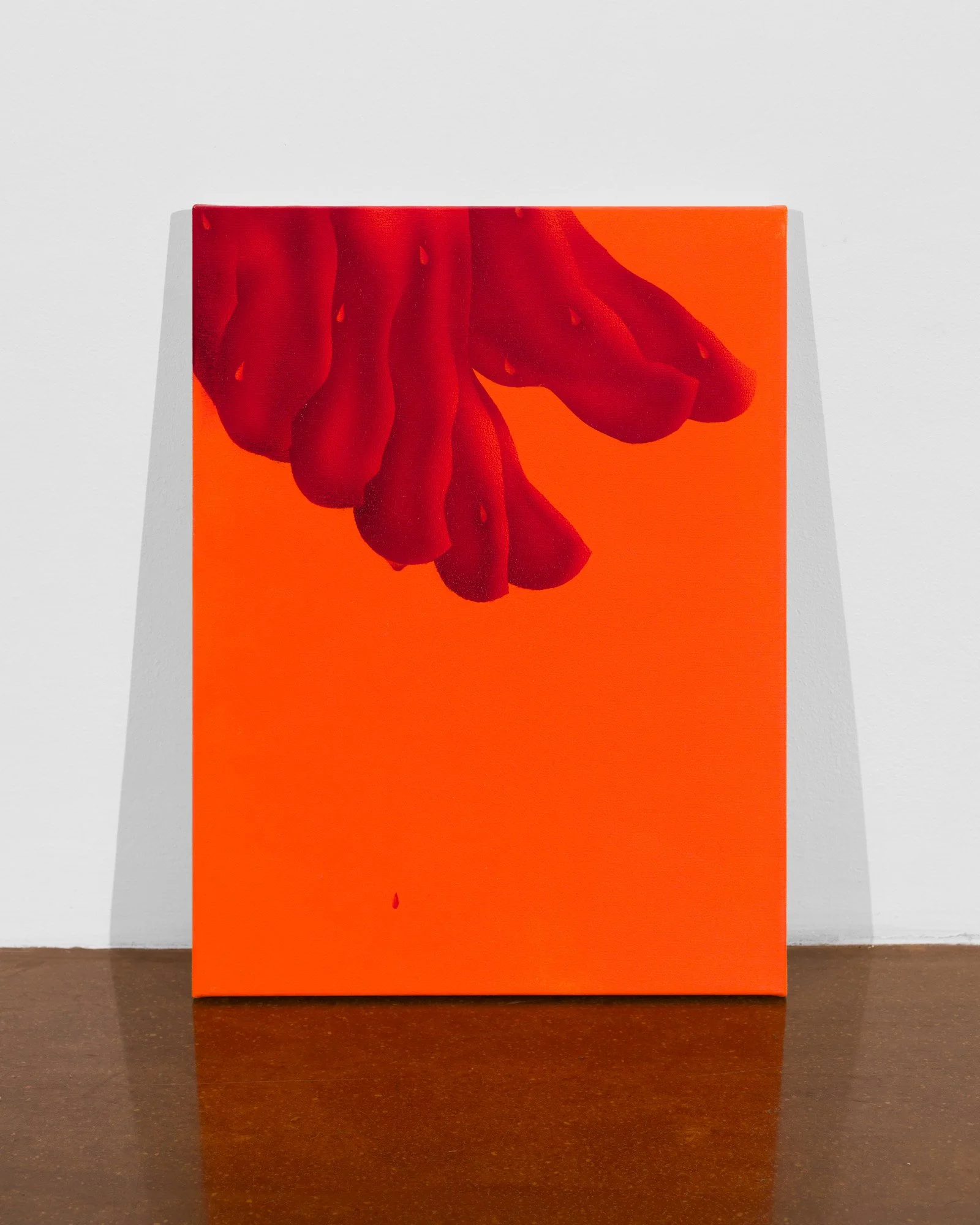

Post-internet painting, but without the tired metaphors. Martin Kolář’s diploma work doesn’t point fingers at the digital age, it swims in it. Executed in soft, matte gradients with colored pencil and airbrush, his paintings operate like visual hip-hop: splicing fragments of cartoon nostalgia, virtual architecture, sci-fi tropes, and raw emotion into something rhythmically unstable, but hypnotic.

Kolář describes his world as “postrealistic” , where personal memory, online imagery, and collective visual archives bleed into one. His compositions are lush and meticulous, yet always on the edge of glitch. The characters are often caught in moments of blank reverie or quiet breakdown, suspended in sterile environments that recall both childhood bedrooms and uncanny video game lobbies. Nothing is entirely safe, nor entirely serious.

These are not narratives with clear beginnings or ends. They are “liquid,” as the artist writes, built on associative logic, ironic distance, and melancholy undercurrents. Martin Gerboc, in his critical review, notes the way Kolář orchestrates space and color like beats in a track. Each painting pulses with its own groove, sometimes ornamental, sometimes confrontational, always aware of its own image-making.

At their core, Kolář’s works wrestle with identity in an overstimulated world. They’re not cautionary tales. They’re not utopian visions. They’re snapshots from inside the noise, where nothing quite fits, but everything is charged.

Mai (Magdaléna Rajchlová)

Delicate limbs, paper-thin skin, and fractured gestures lie scattered across the floor. Some are crumpled, others curled like they’ve just let go of a body. In this fragile installation, Mai (Magdaléna Rajchlová) paints with red chalk and watercolor on translucent tracing paper, rendering flesh so precisely it feels almost like memory rather than anatomy.

The work deals with trauma not as spectacle, but as residue. It does not dramatize pain. Instead, it leaves it quietly folded into the room, inviting viewers to step around it, or into it. These aren’t full figures. They’re fragments, like what's left after something has been processed, survived, or repressed.

It’s strange, intimate, and deeply human. A drawing practice that becomes a kind of shedding. A body present not through posture, but through absence. A work that touches, gently, before it disappears again.

Maximilián Aaron Mootz

Lime scooters, remade from invasive wood, appear here not as urban convenience but as sculptural cautionary tales. In Mootz’s Lame, the iconic e-scooter is stripped of its sheen and rebuilt in white-stained black locust and tree-of-heaven wood, materials that, much like the vehicles themselves, thrive in neglected spaces.

The objects sit between critique and absurdity. A public intervention staged near Charles Bridge shows the wooden scooters placed on the street, confusing tourists and drawing amused looks, until Prague’s municipal services roll in and haul them away. In another video, a self-built fence mimics the urban anti-paths familiar in Czech cities: makeshift barriers to block organic routes carved by pedestrian desire, often more rational than the ones designed for them.

Where cities attempt control, Mootz inserts dysfunction. His objects are elegant in their failure, stubbornly unusable and poignantly symbolic. The work is less about mobility than about who gets to decide which direction is forward.

Jakub Brázda

Jakub Brázda’s diploma project centers around a monumental wooden head, carved from blocks of reclaimed timber gathered over several years, some dating back half a century. Rather than aiming for realism, Brázda embraces intuitive, detail-free modeling, sculpting by feel rather than thought. Inspired by the tradition of taille directe, he shapes each segment individually, balancing on the edge of what can be removed, until only what “doesn’t bother him” remains.

Next to the sculpture stands an unexpected companion: a rabbit hutch from his family garden, transformed into a self-service vending machine. Inside are souvenirs and small sculptures derived from the main head, available via QR code or coin box.

Brázda’s work is both physical and conceptual, grounded in rural materiality, yet aware of sculpture’s history, its scale, and its performance.