AVU SUMMER 2025

Every summer, we return to the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague to see what has surfaced. The final exhibitions—known as klauzury—aren’t group shows in the traditional sense. They’re solitary culminations, each reflecting months of focus, tension, and intuitive searching.

What’s shown here isn’t always polished—but that’s not the point. These aren’t works tailored for the art world, or shaped to fit external expectations. They’re made from something closer: necessity, instinct, the need to say something—often before the artist even knows what that something is.

This year’s selection isn’t defined by a shared style or theme. It’s held together by urgency. Some works take the form of mourning, others of confrontation, tenderness, irony, or refusal. What they share is presence. You can feel the artist inside them.

In many cases, painting isn’t just a medium—it’s a way of existing. A method of staying present, processing emotion, remembering. These works don’t perform. They endure.

We’re not here to judge or rank. The goal isn’t to say who was “best.” It’s to listen. To stand still long enough to notice what’s being said—through color, rhythm, material, silence.

Best of AVU isn’t a verdict. It’s a cross-section. A collection of rooms, ideas, and inner landscapes—briefly opened to the world.

Ema Kissová, Matěj Kučera, Dominika Fišerová, Jolana Hartmannová

For the third consecutive year, this space has become home to some of the most compelling sculptural installations coming out of AVU. Once again, students from Vojtěch Míča’s studio have chosen not to separate their works into solitary corners, but to weave them into a shared topography—each voice distinct, yet resonating together.

Ema Kissová’s sculptural practice moves between myth, matter, and intimacy. Trained in the Studio of Figurative Sculpture and Medals under Vojtěch Míča at AVU, she works primarily with stone—Carrara marble, serpentinite, and andesite—carving figures that are both abstracted and emotionally charged. Her recent works explore themes of tenderness, transformation, and dialogue: a reclining female form softened by the memory of Henry Moore; a serpent devouring its own tail, invoking the cyclical flow of life and death; a pair of stones in quiet conversation. Whether referencing ancient symbols or personal experience, Kissová’s sculptures ask how material can embody emotion—not as metaphor, but as a physical echo. Her attention to detail is tactile and meditative, turning each work into a site of both presence and reflection.

Dominika Fišerová turns landscape into matter—literally. Her recent work focuses on the red earth of the Podkrkonoší region, rich in iron and memory, which she grinds, mixes, and applies to paper and sculptural surfaces. The material process is quiet, ritualistic, and deeply embodied. For Fišerová, color is not a symbol but a residue: something that clings to skin, to shoes, to memory. What begins as a pigment becomes a language—a way of translating place through touch. Her installation brings together prints, soil-based paintings, and sculptural reliefs, each bearing the slow rhythm of erosion and return. Red is not decorative here—it is elemental. The work holds the tension between beauty and heaviness, support and sorrow, echoing the landscape itself: generous, brutal, and unshakably formative.

Matěj Kučera, in his personal work, focuses on the theme known as POHUP – a series of rocking animals placed on various uneven surfaces, or "cradles." In these objects, he explores the contrast between playfulness and the “untouchability” of sculpture, as well as between functionality/design and the unique expressive nature of an artistic artifact. He sees a particular uniqueness in the cradle compared to classical kinetic art – he is freed from complex technologies or lengthy measuring processes and can instead concentrate solely on the center of gravity and how the sculpture vibrates, trembles, and operates in space. He is also deeply engaged in the creation of architectural sculptures, along with their visualizations and designs intended for public spaces.

Ema Kissová's Instagram

Jolana Hartmannová's Instagram

Matěj Kučera's Instagram

Dominika Fišerová's Instagram

Sára Konečná

Sára Konečná’s latest series unfolds in the charged, intimate space of a sauna—a site meant for relaxation, yet filled with tension. Her paintings reflect this paradox: the heat meant to release the body becomes a pressure point in itself. How far do we push ourselves in search of ease?

The environment is key to Konečná’s practice. Each project begins with a place—not just as a setting, but as an emotional register. Here, the sauna becomes a stage for bodily awareness: glances, discomfort, breath, exposure. In this setting, Konečná turns to cropped figures, isolated hands, anonymous backs. The heat is visible; so is the unease.

She writes about the smell of scorched wood, the awkward shuffle of shared space, the jarring stares of older men, and the constant opening of the door that lets all the warmth escape. The works carry this psychological edge, but with a hidden smile—tense moments rendered with soft gradients and controlled gesture.

It’s hard to relax, the artist suggests, when you’re busy pretending you already have.

Kateřina Kábová

Kateřina Kábová paints atmospheric scenes that hover between landscape and interface, meditation and anxiety. Her latest works extend her ongoing exploration of how digital reality, environmental unease, and emotional fragility overlap and mutate in contemporary perception.

In Kábová’s paintings, the sun is no longer romantic. It blazes, glitches, pulses unnaturally through wire fences or scorched terrain. Circles repeat like digital lenses, surveillance loops, or icons stripped of function. Yet nothing feels ironic. These are not parodies of the sublime—they are what’s left of the sublime after too much screenlight, too much distance, too much looking.

Kábová’s visual language borrows from Romantic landscape painting, early 2000s desktop aesthetics, and the quiet violence of industrial edges. She paints with care, even tenderness, but also with tension—each brushstroke balancing illusion and interference, memory and distortion.

Her work doesn’t offer solutions. It creates climates—places to sit with unease, to hold both beauty and exhaustion in the same frame.

Leonard Železo

“I look at their faces and try to read how they actually feel. I dress animals in human clothes and watch them suffer. Because in that moment, we share something. Neither of us wants to be here.”

Leonard Železo’s dog portraits are not ironic. They’re witnesses. Constructed from image scraps and Instagram feeds, these painted canines take on quiet dignity: stiff, resigned, a little ridiculous. Rendered with old-school portrait lighting and technical care, they stand in as stand-ins—for the artist’s own discomfort, for shared awkwardness, for the strange loneliness of performance.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, Železo installs a wall of intimate miniatures—queer-themed, hand-framed, often absurd. Delicate ink drawings, framed in gilded kitsch or fake fur, lure viewers in with humor or texture, before revealing symbols of kink, vulnerability, or pleasure. Tiny penis studies, treated like souvenirs.

This isn’t a separation of “serious” and “not serious” work. It’s a practice rooted in detail, intimacy, and unapologetic self-definition. The dogs help carry what words sometimes can’t. The frames make space for slow glances. Together, they build a room that sees you—even if it doesn’t ask to be seen back.

Anna Krištofíková

After returning from a six-month residency in New York, Anna Krištofíková began painting from memory—but not just to recall the city. Her canvas A Memory Has Fallen, Make a Wish reimagines a place she walked past nearly every day on Manhattan, now cloaked in a soft pink haze. It is a romanticized recollection: the figure is headless, absent from the place it once inhabited, while a black-and-white mask from the present observes from above—emotionless, uninvited.

From the mask, Krištofíková’s new cycle turned toward symbols of protection: metal, locks, keys, shields. The diptych Wild at Steel Heart explores the urge to guard one’s emotions—not only from others, but from oneself. Keys appear, but never clearly match their locks. The artist describes this uncertainty: “I don’t know which key fits which lock—or if opening any of them would even help. But I’ll only know once I try.”

Her work is both vulnerable and armored, with surreal gestures and emotionally encoded details. The tension between softness and steel is not resolved—only suspended.

Roman Košťál

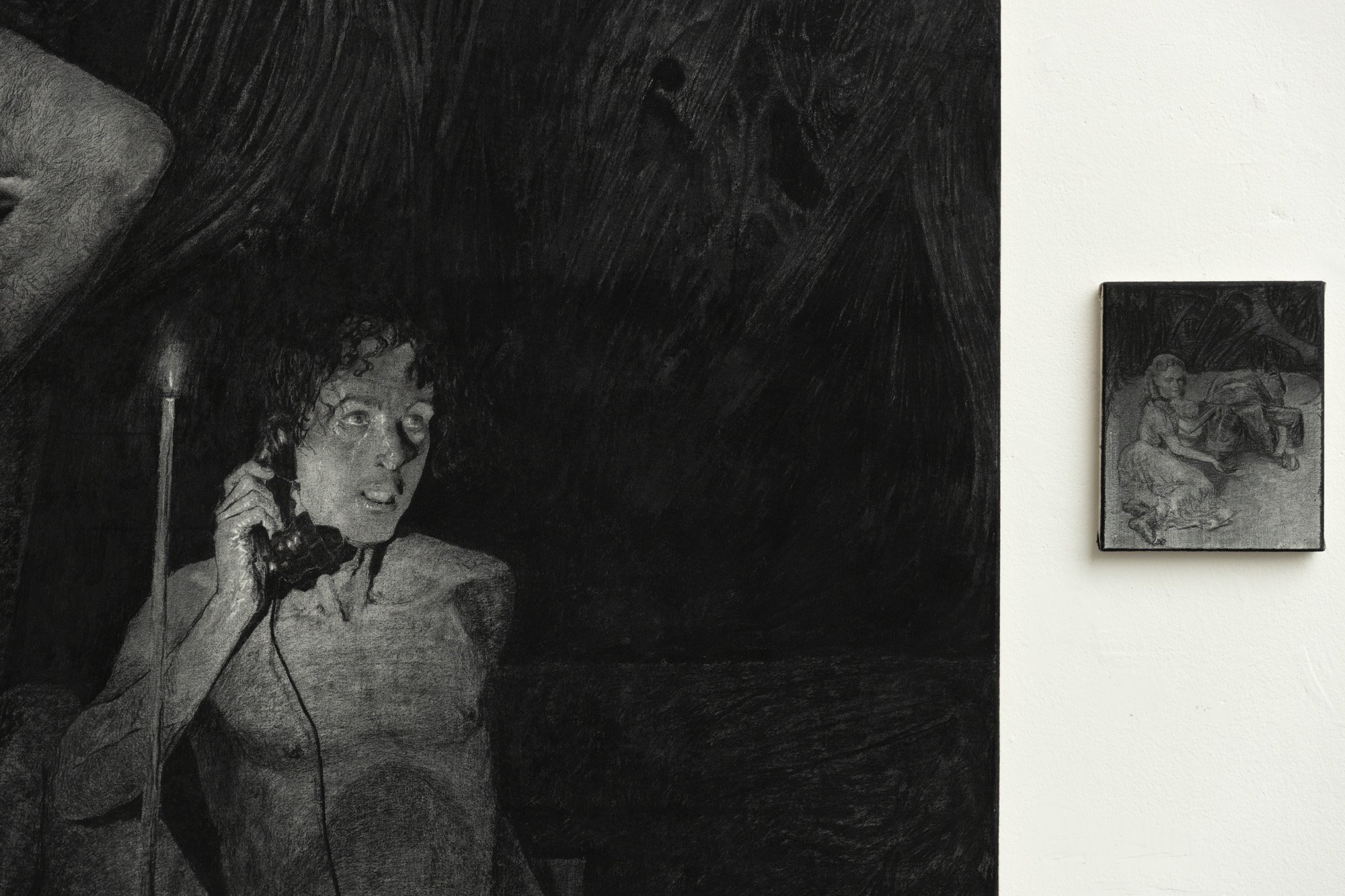

In the centerpiece of his ongoing series Sons, Devour Your Fathers, Roman Košťál constructs an image suspended between grief, power, and psychoanalytic tension. The work is born from the death of his father, but refuses catharsis. Instead, it presents the paternal figure not as a person, but as a fractured symbol—absorbing archetypes of dominance, vulnerability, and loss.

The large-format charcoal drawing shows two figures in an intimate but unresolvable scene. One sits—naked, wary, disarmed—holding a vintage telephone, an object both archaic and intimate. Behind and above him stands a second, more imposing figure, half-draped, sword in hand, half-shadowed. Their relationship is unclear. Are they lovers? Enemies? Father and son?

Košťál calls the moment “a sexualized announcement of a devastating message.” The scene echoes both religious iconography and psychoanalytic staging. The seated figure may be a Christ-like sufferer, but also a son awaiting judgment. The standing one—part executioner, part witness—may be a father, a vampire, a god. Candles flank the stage, but offer no moral light. The viewer is left circling the question: who is the victim, who the aggressor, and are they not, in fact, the same?

The image’s atmosphere is built not through detail, but through charcoal’s slow sedimentation. Košťál works not as a draftsman, but as a painter of darkness—letting shadows swell until they form shape, weight, presence. The surfaces feel scorched, charred, almost fossilized. He has called them “burned branches,” and indeed they seem less drawn than excavated.

Beyond the biographical origin lies a broader reflection: on the symbolic death of the father figure, on generational power shifts, on the struggle to separate one’s identity from what has been inherited. The oedipal reading is not incidental, but deeply embedded. Košťál mentions discovering the psychoanalytic parallels only after the work’s completion—as if the unconscious had already written them in.

The image resists easy resolution. It is neither narrative nor allegory, but something slower and more psychological: a ritual performed in silence, a reckoning without conclusion. Like mourning itself, it circles back on itself, dark and unfinished.

Alongside this central work, Košťál created a parallel series of 21 smaller charcoal paintings exhibited as part of his solo show Bad Luck at HIDDEN Bořivojova (June 2025). These works, including the painting VAMP, are linked more by atmosphere and symbolism than by narrative. They carry over formal elements—ritualized gestures, candlelight, intimate violence—but shift toward folklore and archetype. If Sons, Devour Your Fathers is a psychological descent, VAMP and its companions operate more like talismans: dense with suggestion, myth, and unease.

Together, they form a personal mythology—equal parts lament and invocation.

Anastasiia Lisnycha

Originally from Ukraine, Anastasiia Lisnycha has lived and worked in Prague since 2022. Her practice centers on sculpture, often combining concrete and metal—weight and fragility—in quiet tension. Her works are less about illustrating ideas than about translating the invisible: interior states, philosophical inquiry, and spiritual attention.

The ongoing series The Garden of Thoughts explores the mind as a cultivated space. Thoughts grow like plants—some wild, some deliberate, some toxic. The viewer is placed within a metaphorical orchard, where care, pruning, and observation become existential acts.

At its heart lies a reflection on inner ecology: how the interior shapes the exterior, and how symbolic structures can carry lived experience. A recurring influence is the Ukrainian philosopher Hryhorii Skovoroda, who wrote:

"God is like a rich fountain that fills vessels according to their capacity. And above the fountain is inscribed: ‘Unequal equality for all.’”

Lisnycha’s sculptures and reliefs do not offer answers. Instead, they stand still—guarding the threshold between the concrete and the contemplative.

Martin Mlateček

These paintings aren’t declarations. They’re residues. Byproducts of something already gone. Martin Mlateček paints at night, often in the street, chasing not images, but atmospheres—specifically the slippery, electric disquiet of Prague’s nocturnal hours. What remains on the canvas is a study, a fragment, a surface. The real event, he says, already happened.

A guy offers heroin at 5am. A drunk wants to talk aesthetics. Commuters shuffle past, half-awake. One man watches him paint for over an hour. That’s the art, Mlateček suggests—not the “nice painting” on the wall, but the strange, shared space of time, vulnerability, and late-night proximity. The canvases are keepsakes from those moments—unspectacular, unresolved, real.

There’s no heavy narrative here. Just streets. Sodium lights. A refusal to romanticize or condemn. Žižkov, he adds, isn’t a place to avoid. It’s the friendliest part of Prague.

Klára Korbelová

In this striking diptych, Klára Korbelová navigates the blurred terrain between memory, addiction, and fractured identity. The two large-scale canvases—each 300 by 150 cm—form a visual dialogue between internal voices, between what is felt and what is endured.

The first painting renders a recurring sleep paralysis episode: a familiar demon perched on the shoulder, whispering into the ear. It’s not dramatic in gesture, but quietly oppressive—capturing the slow, manipulative gravity of dependence. The second canvas moves toward aftermath: remnants of a chaotic night, still glowing with the warmth and color of intoxication, but emptied of euphoria.

The series She and I emerged as a progression from earlier, more fragmented visual memories of alcohol dependency. Here, the focus has shifted—from past to present, from anecdote to psyche. Through bold color and heavy patterning, Korbelová builds a space where intimacy becomes unstable, and the self is constantly split.

Anna Helová

This body of work continues Anna Helová’s ongoing interest in landscape—not as scenery, but as experience. Walking through cities or forests, she follows the rhythm of her own steps. One foot, then the other. Movement becomes meditation, and that rhythm carries into the paintings: lines that repeat, trees that echo, colors that pace each other across the canvas.

Alongside this visual cadence, there is also stillness. Resting, lying down, small pauses in daily life. Everyday objects like necklaces or familiar rooms appear, not as symbols, but as part of a personal visual grammar. In this semester’s work, Helová has also begun to explore figuration—an unfamiliar but promising terrain.

These are not narrative paintings. They do not ask to be explained. They function autonomously, like music: driven by internal logic, emotion, and form. Content is present—but not pressing.

Lucie Hošková

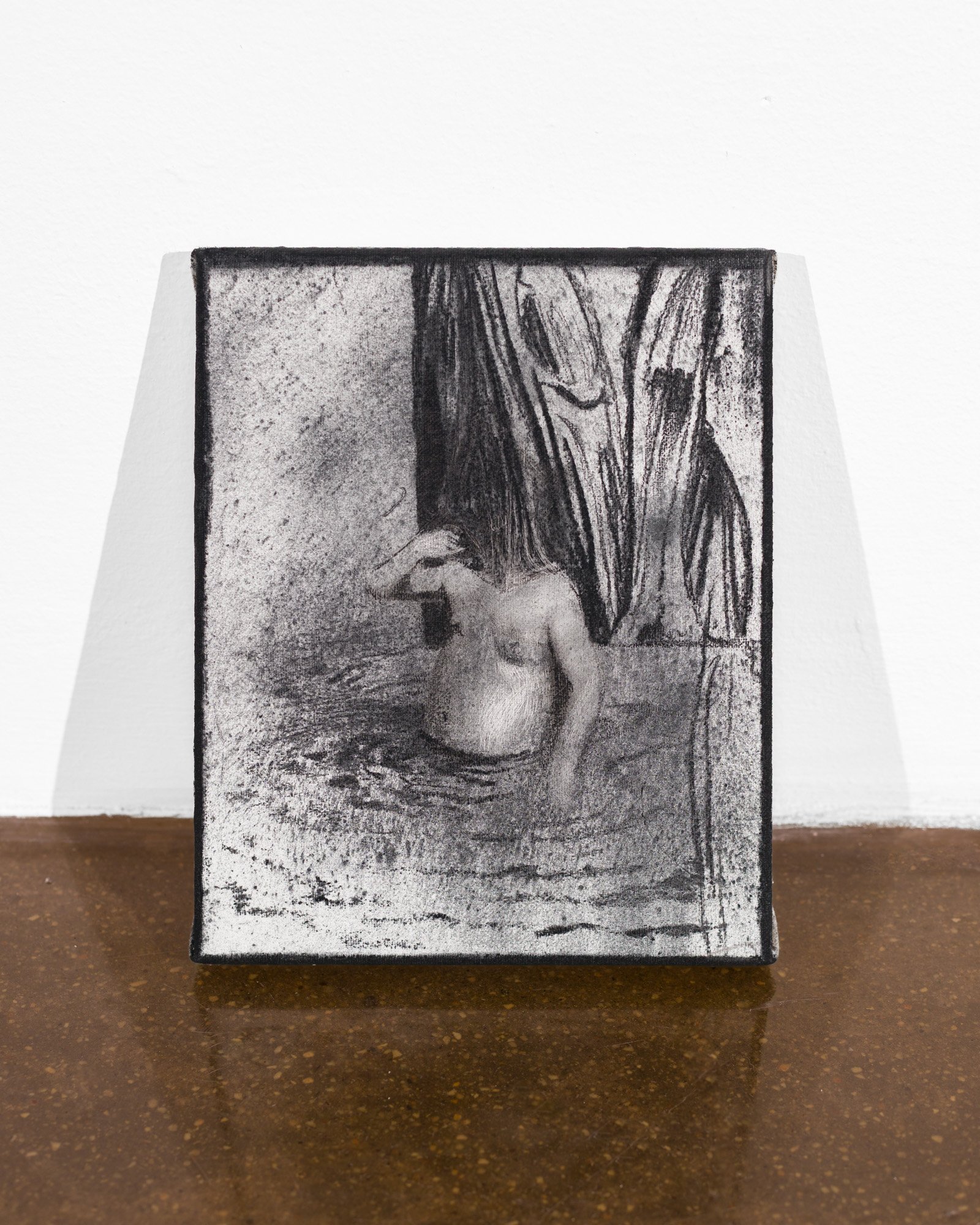

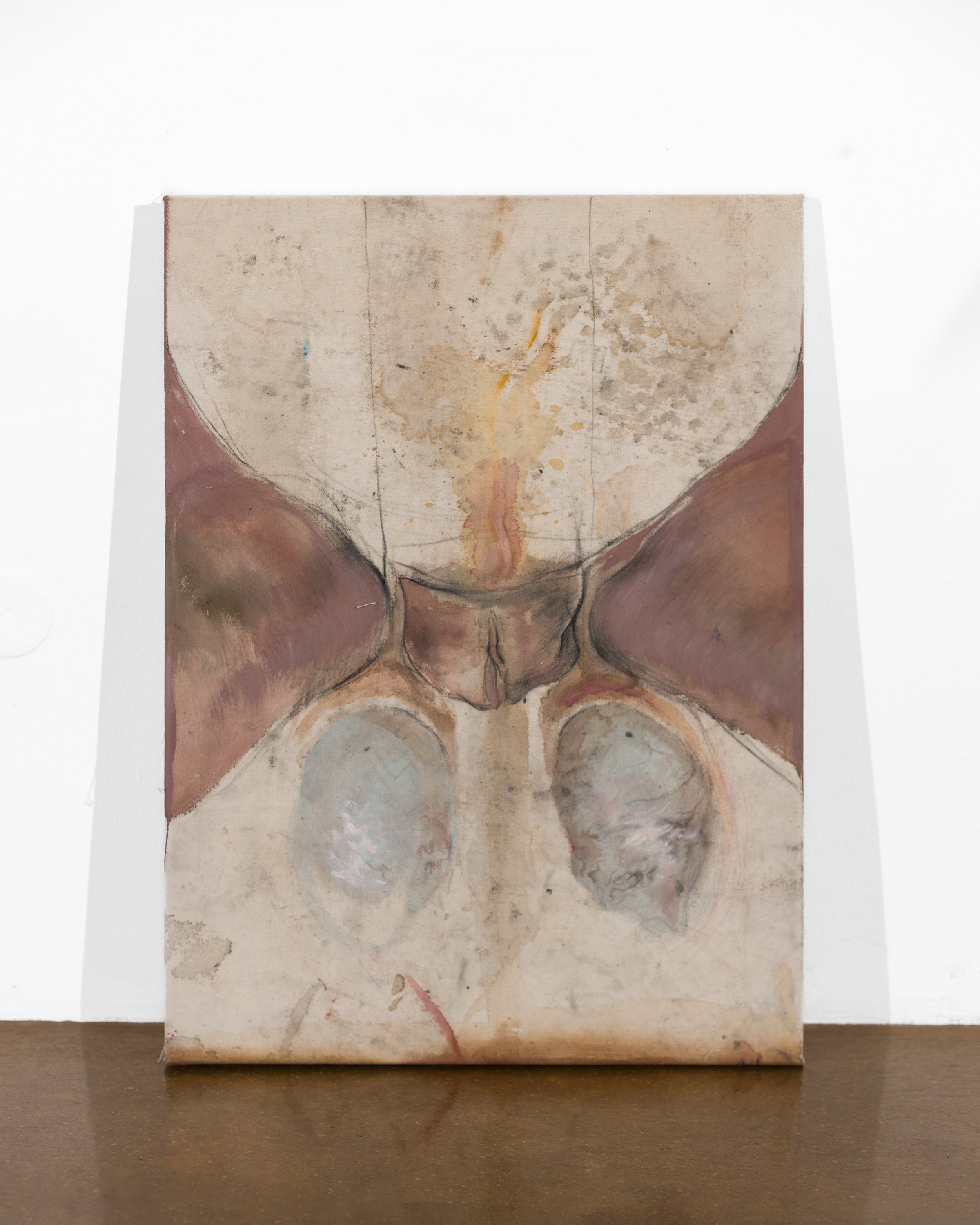

In this intimate and tactile installation, Lucie Hošková returns to the themes of death, birth, and transmutation—drawing from her recent semester at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where she studied under Emmanuel Van der Meulen and immersed herself in anatomical and memorial spaces such as Musée Fragonard, the Musée des moulages, and the Père Lachaise cemetery.

Her central diptych contrasts a black canvas evoking the head of the deceased with a white one referencing a section of placenta. Around them orbit looser forms—stained and textured, resembling bodily fluids and layers of soil. The narrative is subtle but precise: a soul departing its body, remnants settling in the earth.

There is no overt symbolism here, only slow material suggestion. Through restrained gesture and darkened palette, Hošková frames the body not as spectacle, but as cycle.

Ivan Lendiaiev

Ivan Lendiaiev’s presentation unfolds in two distinct but interconnected parts: a quiet procession of drawn female figures, and a single monumental painting—a crowned, seated form rising from a mass of horses.

In the Girls series, vertical ink drawings made with a tattoo machine depict generalized female types—elegant, ornamental, and emotionally distilled. Playfulness, calm, curiosity, self-possession: each figure stands alone in her presence, not in her identity. These aren’t portraits. They are stylized carriers of emotional states—silent, poised, and constructed with reverent precision.

Alongside them stands a large-scale painting: Throne of Memory. A solitary androgynous figure sits atop a fusion of horse heads, draped in red cloth, wearing a helmet shaped like a crumbling house. The atmosphere is thick with ambiguity. The figure is neither masculine nor feminine, neither warrior nor ruler. The tower on the helmet becomes a reliquary—for childhood, for home, for a paradise lost. The horses below are not noble beasts but a single merged body—weight, instinct, memory, myth.

The painting resists time. There are no modern objects, no digital hints, no ironic gestures. Instead, it borrows its language from vanished epochs: armor, symbolism, silence. It does not narrate—it haunts. Like the drawings, it works not through story but through stance.

Together, these two gestures—procession and throne—frame Lendiaiev’s visual world. On one side: repetition, rhythm, figuration as ornament. On the other: myth, monument, and an overwhelming stillness. What links them is presence. A refusal to explain. A commitment to seeing what remains when words no longer suffice.

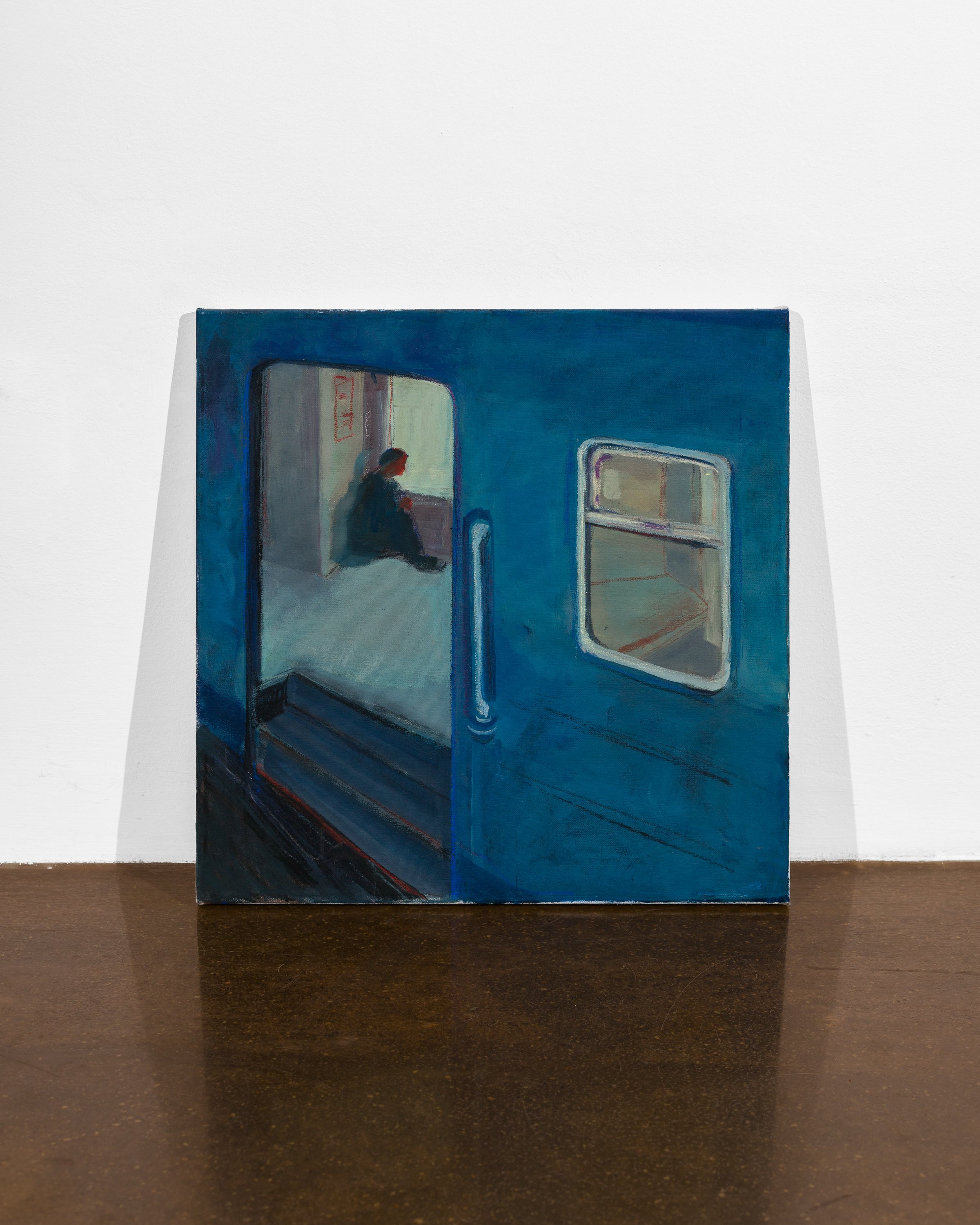

Anna Banytiuk

In her latest works, Anna Banytiuk shifts from the smaller, more intimate studies of her semester work into larger canvases that retain the same emotional charge—but with a softened palette and quieter tone. The move to scale doesn’t dilute her sensibility; instead, it opens space for stillness and nuance.

Drawing on personal memory and shared cultural habits, her paintings reflect a specifically Ukrainian experience of daily improvisation. Shortcut captures a woman ducking under a train—a familiar, if precarious, act in post-Soviet transit culture. Parents shows her mother and father testing a window shade, a scene mundane yet emotionally resonant. These are not grand narratives, but moments held in careful balance between realism and metaphor.

There’s tenderness here, but also distance. The figures blur into shadow, gesture into symbol. The emotion is never overplayed—but it lingers.

Klára Hartlová

In her installation, Klára Hartlová builds a melancholic threshold—a fragile zone between memory and forgetting, interior and exterior, self and dream. The space is inhabited not by figures, but by their echoes: dried roots, moss, a collapsed bed, and a cascade of ultramarine paintings that seem to breathe decay and quiet persistence.

The work weaves together elements of painting, natural matter, and domestic objects to create a world suspended in dream logic. Vegetation creeps through painted surfaces and seeps into household linen, suggesting the collapse of familiar boundaries. The body is absent, yet everywhere implied—a vanishing point around which the world softens, blurs, and reshapes itself.

Hartlová’s visual language feels both archeological and emotional. These are ruins of an inner world, slowly being overtaken by the cycles of decomposition and growth. There is no clear narrative here, only a recurring sense of return: to a room, to a memory, to a silence that never fully fades.

Jakub Hons

In Depository of Future, Jakub Hons turns the irreversible disappearance of glacial forms into an imagined museum. Five abstract marble sculptures, shaped by hand and steel chisels, stand like frozen relics—captured at the moment just before melting.

Inspired by the accelerated collapse of glacial ice sheets, Hons uses the physical resistance of Carrara and veined Turkish marble to mirror the tension between human agency and geological scale. His method—intuitive carving, guided by the natural block—re-enacts erosion, simulating the emotional and physical labour of witnessing planetary loss.

The installation’s modular steel armature evokes archival shelving: a system of containment built to preserve what is already gone. These are not faithful representations of icebergs, but rather imagined remnants—half natural, half man-made. Like the Anthropocene itself, they carry the traces of both violence and care.

Maria Vasylieva

A dusty roadside wreck becomes a quiet monument to the violence of progress. In this haunting installation, Maria Vasylieva assembles fragments of twisted metal, industrial debris, and something more fragile: casts of animal embryos, taken from real creatures killed by cars.

Each sculpted form is delicate, fetal, nearly lost among the mechanical parts that surround it. Yet the work never feels didactic. Instead, it presents a silent standoff between two timelines — one of biological life, the other of machines and extraction.

The numbers are specific: an estimated 144,000 hares die on Czech roads every year — nearly 40% of the population. But Vasylieva’s installation speaks more broadly to the slow catastrophe of the Anthropocene, one that began not with the combustion engine, but with the first tool.

This is not a nostalgic elegy. It’s a cold, dust-choked warning. One that suggests, with brutal tenderness, that we are already living inside the crash.

Klára Latta

Klára Latta’s clausura installation unfolds in a liminal, scenic terrain—one shaped by demolished homes, stray ruins, and quietly watchful mountains. Hands appear throughout, not as symbols of intimacy but as tools—devices for narration, gestures of control.

Latta draws from the visual language of 1990s computer games, especially their rigid isometric perspective. The result is a series of painted spaces that feel strangely distant—like screenshots from a lost digital archive. The works suggest a longing to escape the artificial logic of today’s world: the mapping, tracking, cloud-stored ephemera of everyday digital life. Instead, we’re offered a quiet, pixelated longing for something less mediated.

Despite their flattened surfaces, the paintings invite projection. They don’t depict stories; they wait for them to emerge. And within their constructed distance, the viewer may suddenly find themselves—suspended in a place that doesn’t exist, yet feels oddly familiar.

Marek Mirčev

In his current practice, Marek Mirčev explores the sculptural medium of relief as a way to record—and disturb—linear understandings of time. His works combine geological, human, and imagined strata, resulting in pieces that resemble both ancient ruins and speculative archives. Neither fully abstract nor overtly narrative, they dwell in an unresolved zone between object and memory.

Material is central. Found debris, organic matter, and constructed surfaces are combined into low-relief compositions that appear excavated rather than made. Texture, weight, and erosion are not only formal tools but carriers of meaning. These surfaces invite reading—visual, tactile, emotional—and evoke a memory that may be personal, collective, or entirely fictional.

Mirčev’s installations often feel like archaeological scenarios. But they offer no key, no legend. Instead, they hint at tension: between nature and fabrication, past and present, knowledge and loss. His reliefs are not monuments, but porous traces—remnants of what was once felt, and what still might be.

Nika Brazhnyk

Nika Brazhnyk’s folding screen presents a silent procession of performers: Pierrot, Harlequin, and other half-imagined characters who walk the line between theatre and myth. The figures are suspended in gesture—poised, collapsed, drifting—as if caught between acts or emotions.

The work meditates on duality: joy and melancholy, expression and concealment. Pierrot and Harlequin appear not as opposites, but as reflections—each emotion containing the seed of its twin. The screen itself, traditionally used to divide or shield, here becomes a stage: revealing through fragmentation rather than narrative.

Painted in warm, earthy tones with restrained movement, Brazhnyk’s figures feel timeless yet fragile. Their drama is not theatrical but interior—a quiet play of masks, longing, and delicate posture.

Anežka Hubatková

Anežka Hubatková’s installation unfolds like a collection of votive offerings—paintings as gestures of hope, grief, and quiet persistence. Each work carries a story, and each story centers on a wound. But also on the possibility of repair.

The compositions are intimate in both scale and feeling. We see troubled lovers, fractured families, buried memories. A son hiding from his violent father in the woods. A mother and daughter sitting before a family cottage, facing ghosts of the past. A wounded foot that carries a narrative. Three women planting a new apple tree to replace two lost lives.

Hubatková’s works are not illustrations of events, but emotional climates. The paint is soft, thick, atmospheric. Faces emerge, dissolve, return. Horses appear—wild or broken—mirroring the delicate push and pull of closeness and control in human relationships. Several works are housed in small boxes, like reliquaries. Others stretch across paper or wood, but never impose. They ask.

The artist describes these works as prayers, and they carry that same duality: both confession and wish. Inspired in part by votive traditions, they hold pain not to display it, but to release it—entrusting it to the image in the hope of transformation.

Matyáš Kořínek

For Matyáš Kořínek, landscape is not simply a subject—it’s a way of perceiving the world. His third-year studio work brings together plein air painting, abstracted cityscapes, plaster and wood reliefs, aquatints, and small poetic gestures, yet all of them orbit one core concern: how to translate observation into something deeper than documentation.

Kořínek works intuitively. Most pieces begin without a plan and evolve through impulse, texture, and rhythm. He describes painting as the most natural medium for him—its fixed format offering, paradoxically, more freedom. Reliefs, which hover between painting and sculpture, serve as a compromise: grounded like a canvas, but spatially active.

Among the works is Storm Code, an imagined, apocalyptic vision of rain falling in lines like a barcode. The painting reacts to a dream, yet remains rooted in the motif of the landscape—this time not as a place of peace, but as a field where perception fractures and meaning becomes unstable. The image is accompanied by a short poem, expanding the visual experience through text.

What unifies this diverse body of work is not style, but necessity. Kořínek admits he often creates without a clear reason—only to discover, afterward, that the reason was there all along. For him, making art is not about proving anything. It’s about staying in motion, searching for a form that can carry inner turbulence.

Barbora Koblasová Černá

Barbora Koblasová Černá constructs a fragile constellation of bodies, gazes, and symbolic ruptures. Her installation doesn’t read like a single narrative, but like a series of held breaths—each painting a quiet scene of emotional containment.

In Potracení, a red-tinted figure slips downward through washes of pigment and vapor. The body is unsteady, barely clinging to its form. Above it hangs an unblinking gaze—Oči jsou místo bolesti—where pain isn’t expressed but rerouted: from muscle to stare, from gesture to witness.

Around these works orbit smaller fragments: cropped faces, horse heads, circular forms. The horses are not majestic—they are weary, titled Unavený jako kůň. They feel closer to myth than anatomy, vessels of projection. In Horse Studies, the animal becomes a proxy: for desire, vulnerability, collapse.

Koblasová Černá’s palette is quiet—dusty pinks, bruised reds, almost whites—but the emotion never vanishes. It just retreats beneath the surface, soaking in. Her paintings aren’t illustrations of trauma; they’re states of aftermath. The pain has passed through the body. What’s left is atmosphere, echo, sediment.

There is no catharsis here. Only attention. Quiet, precise, and disarmed.

Found Something You Love? Let’s Make It Yours

Many of the works featured here are already available in our online store—browse and take home your favorite piece today.

But what if you saw something in the photos that’s not listed online? No problem. If a specific artwork from the installation caught your eye, we’re here to help:

Contact us directly at filip@hiddengallery.cz to check availability.

Arrange a studio visit to see the piece in person and meet the artist.

Get expert guidance to find the perfect artwork for your space.

Don’t hesitate to reach out—whether it’s a piece from the photos or something completely new, we’ll make sure you don’t miss out.