Roman Košťál

Bad Luck

HIDDEN Bořivojova

22. 04. / 22. 5. 2025

After three years of showcasing exclusively international artists, HIDDEN Bořivojova returns to its roots — inviting some of the most distinctive voices from the Czech art scene into the spotlight. Expect raw, intense, and unpredictable encounters.

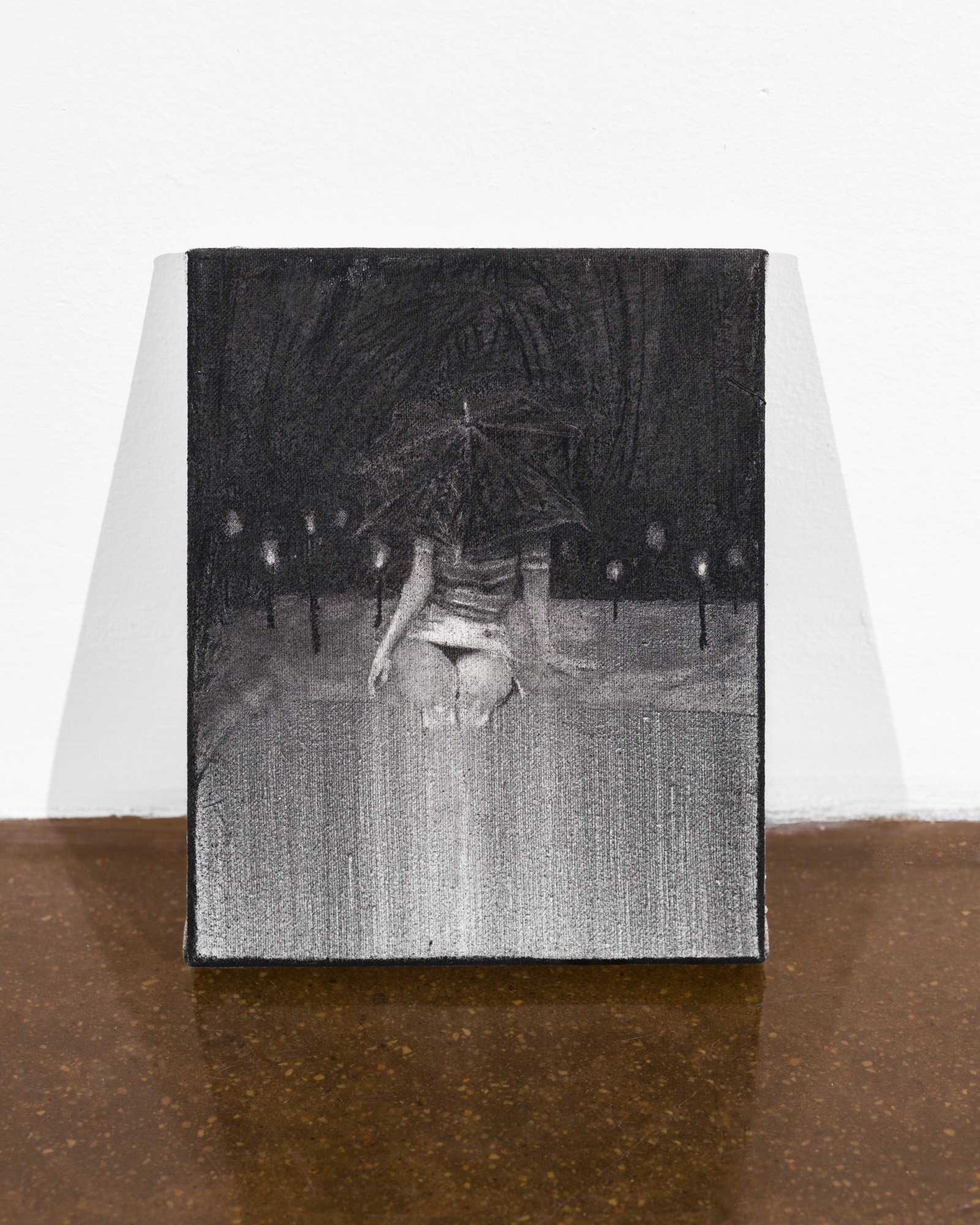

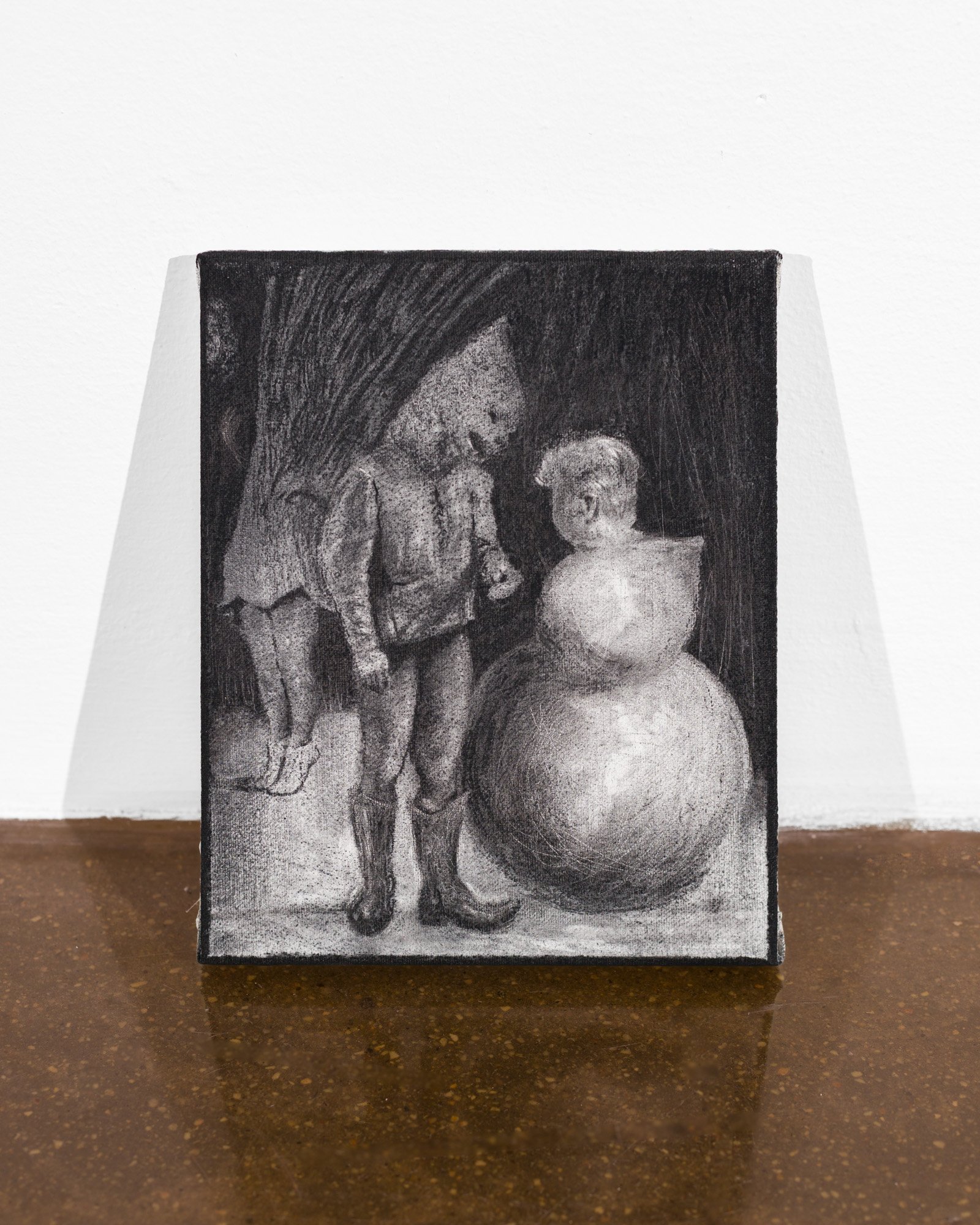

Just as Boëthius wrote about the fickleness of fortune in his Consolation of Philosophy and Niccolò Machiavellidiscussed the role of luck (fortuna) in politics and governance in The Prince, Roman Košťál explores the thorniness of painful misfortune on the canvases of his paintings. The exhibition “Bad Luck” is composed mostly of smaller formats, forming a grand pessimistic mosaic in which each painting represents a minor chord in his grand symphony of tragedy and melancholy.

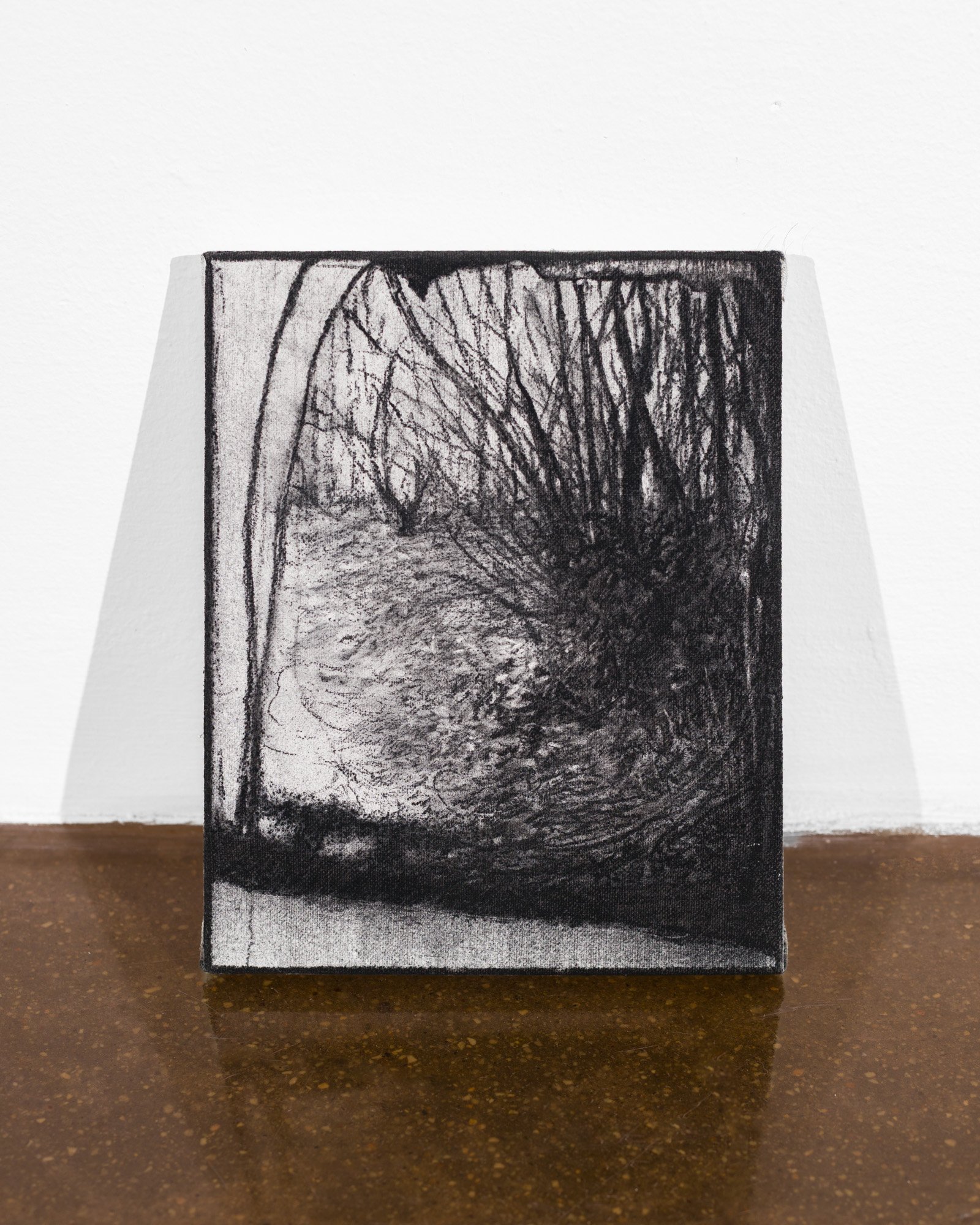

Over the past year, the artist’s style has shifted from mournful, lyrical motifs of a bleak cinematic grotesque toward stronger and more frenetic scenes, filled with omnipresent danger, all executed with a high intellectual standard of visual “language.” It is a gothic folklore on the edge between Midsommar and David Lynch’s psychological thrillers. These occult-cinematic visions (see, for example, the actor Klaus Kinski depicted as the vampire Nosferatu) serve as metaphorical embodiments of the dark sides of the human psyche, and like Braun’s allegories of “Vices” in the Baroque complex of Kuks, they materialize all that is bad within us.

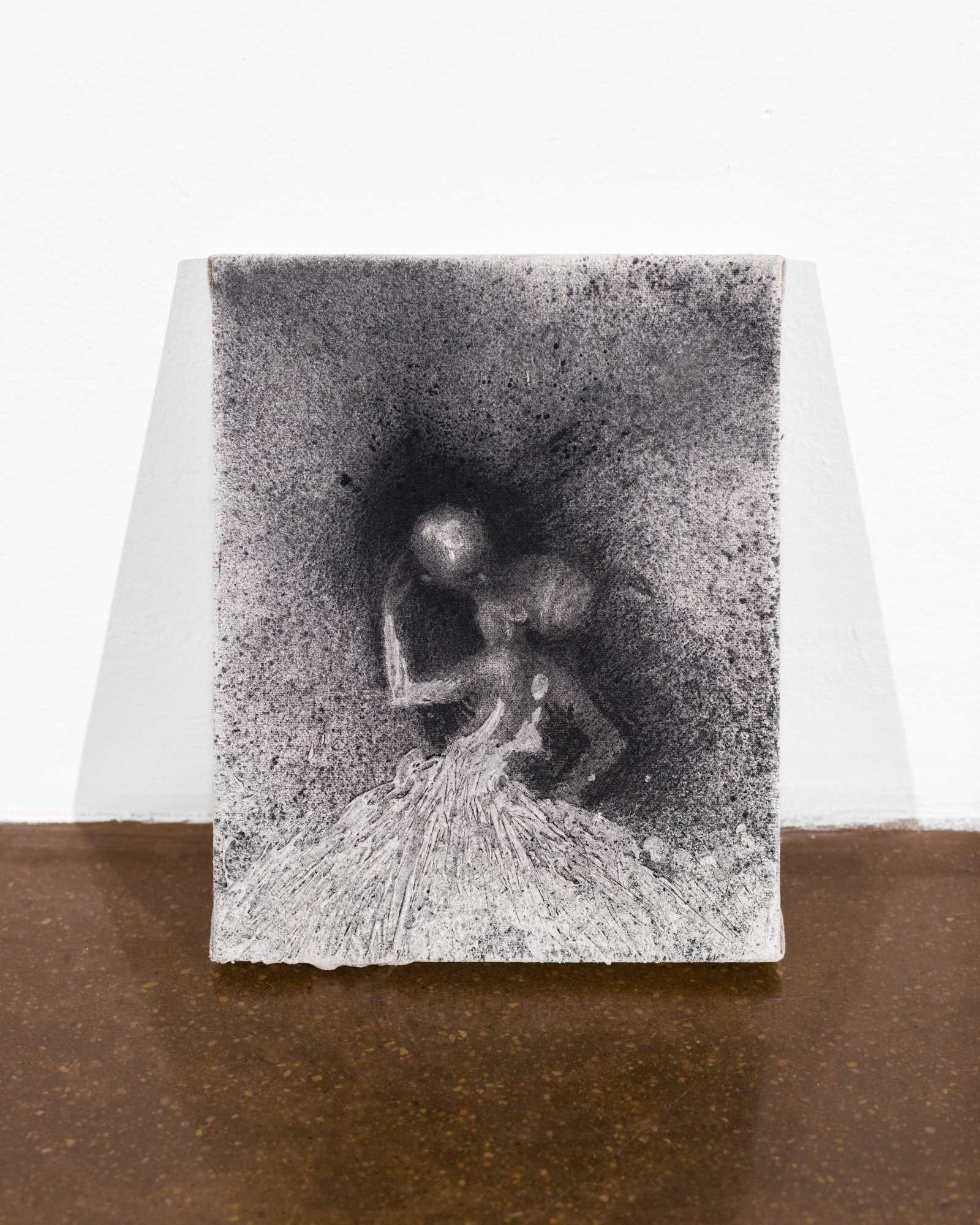

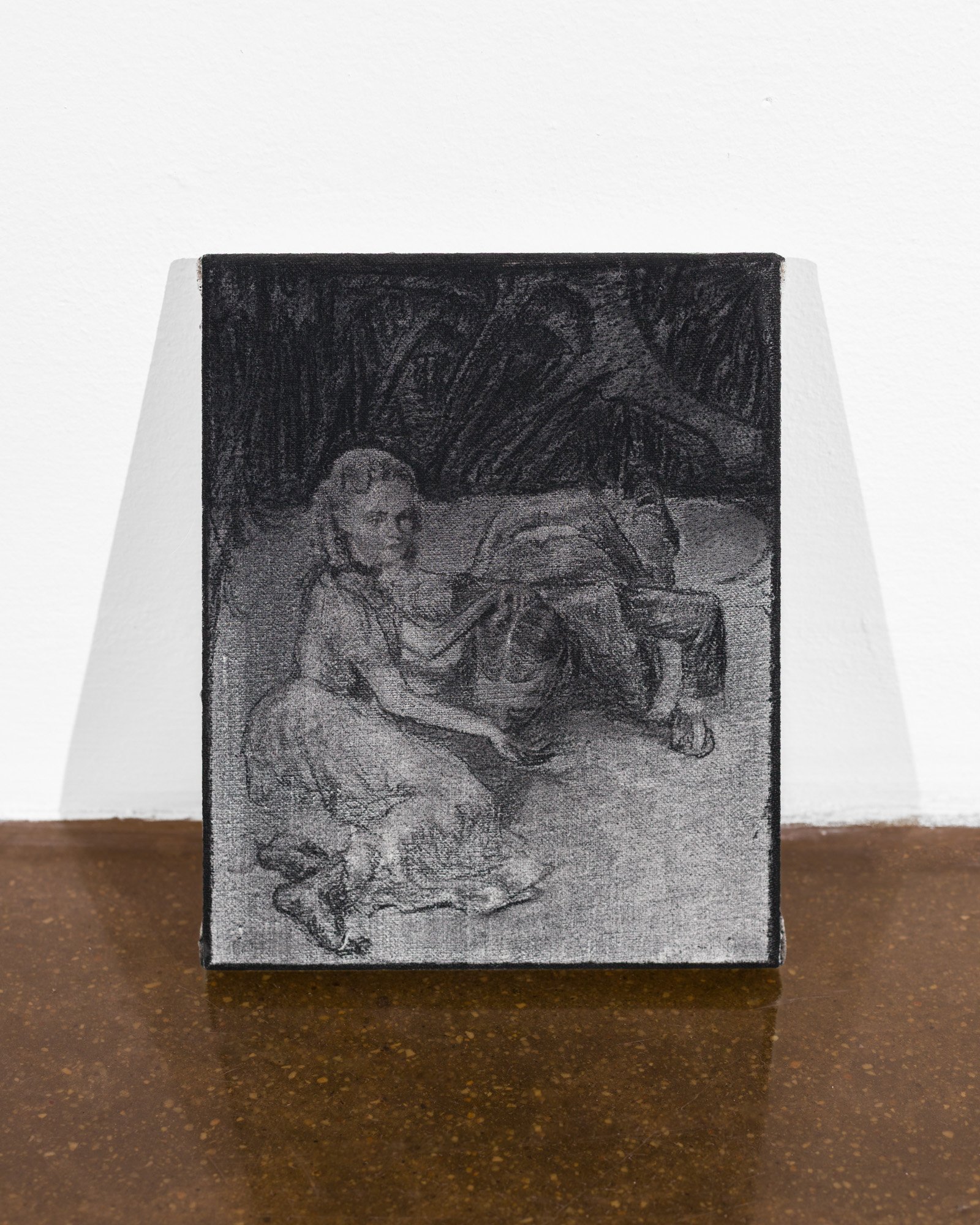

The painting titled “The Fetishist’s Garden” portrays the ghosts of a man and a woman as a dead Adam and Eve, cast out of paradise only to return there after death—only to get lost on the border between the realm of the living and the afterlife. Yet this bizarre scene of two phantoms is merely a backdrop for the ominous figure of a cat with phosphorescent feminine eyes, as if she had leapt straight out of Verlaine’s sonnet “Femme et chatte,” casting a black shadow like a harpoon. In Košťál’s garden, this feline replaces the biblical serpent and thus embodies the Devil himself.

Rollo May, a key figure in American psychology who studied schizoid states, defines in his book Love and Will the fundamental human tendency as the “daimonic”:

“The daimonic is the urge in every being to affirm itself, assert itself, perpetuate itself and grow. [...] It manifests as excessive aggression, hostility, cruelty—those things which most frighten us about ourselves and which we repress whenever possible.”

Košťál deliberately reminds us of these repressed impulses in his paintings, confronting us not merely with a mirror, but with an entire mirror maze we are forced to navigate.

In his works, the painter brings us a cruel gospel: that all happiness is blind chance, and since no one chooses the conditions of their birth (their body, talents, wealth, family, etc.), life itself can only be seen as a perverse lottery. Košťál cynically experiments on the viewer and, like the biblical serpent, offers them the apple of sin—only to snatch it away and eat it himself.

Astrophysicist Stephen Hawking once said that Einstein was wrong when he claimed that God does not play dice. But in the realm of art and imagination, it is we who may throw the dice and cry “Alea iacta est.”

Do it.

– Kamil Princ

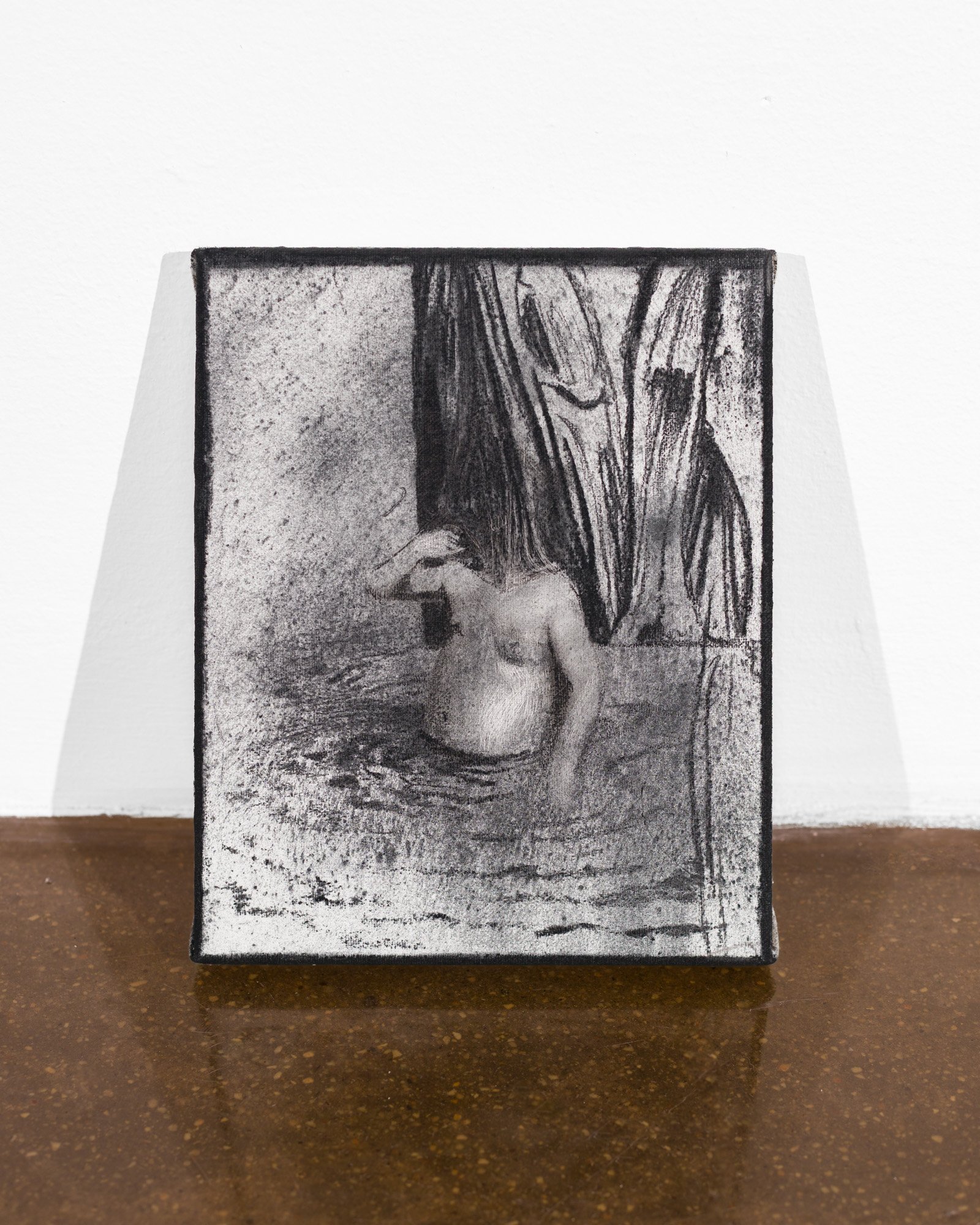

Supernatural Beings & Metamorphosis

These bodies are no longer merely human – they are shifting forms, merging with animals, ghosts, and symbols. Women appear as mythological archetypes, both seductive and threatening. This group of drawings explores the limits of identity through visceral change and surreal embodiment.

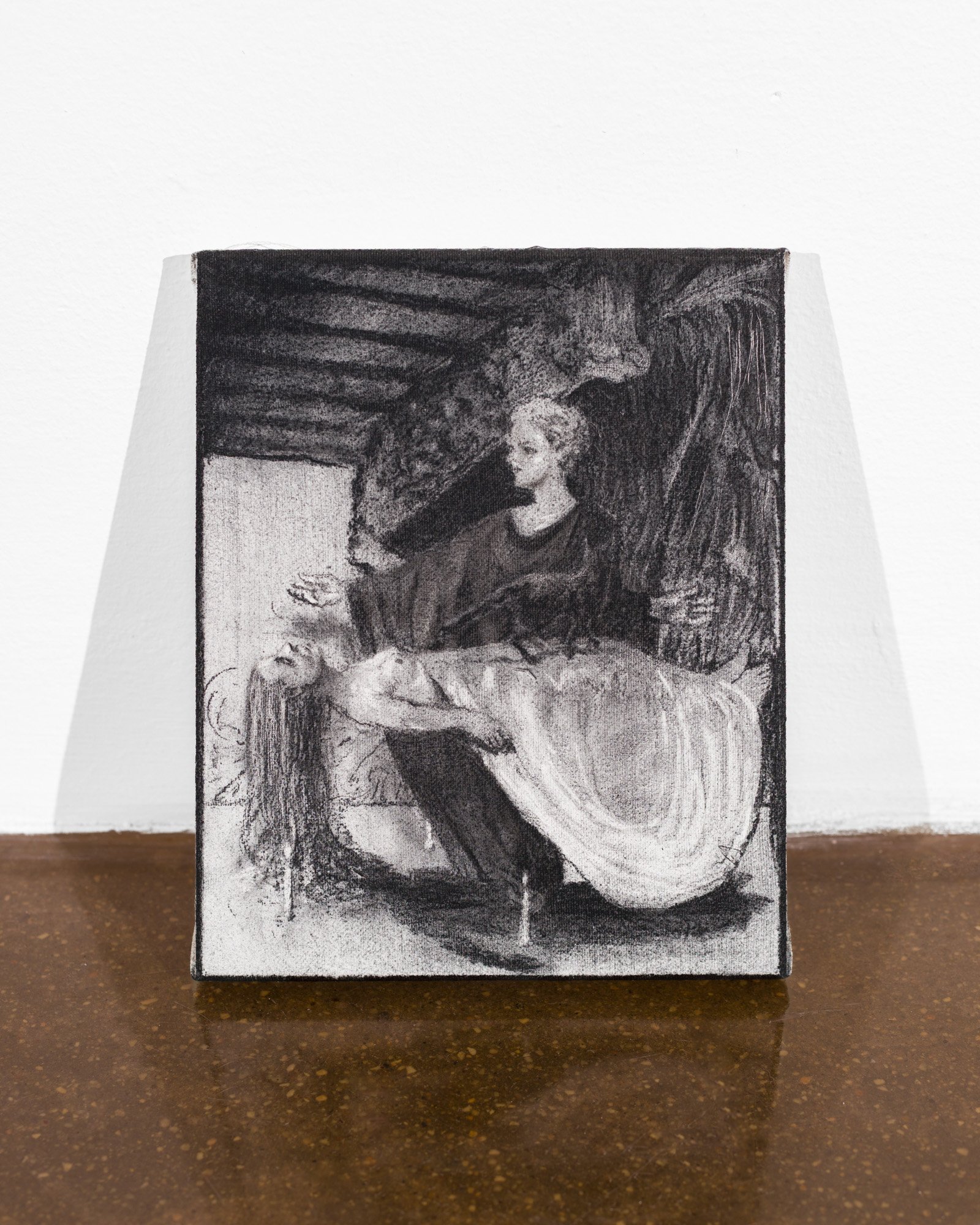

Rituals & Sacrifice

Every figure here is offered – to gods, beasts, or collective memory. These works channel a dark ceremonial energy, where bodies become vessels for transformation. Whether erotic, sacrificial, or bestial, the ritual is central.

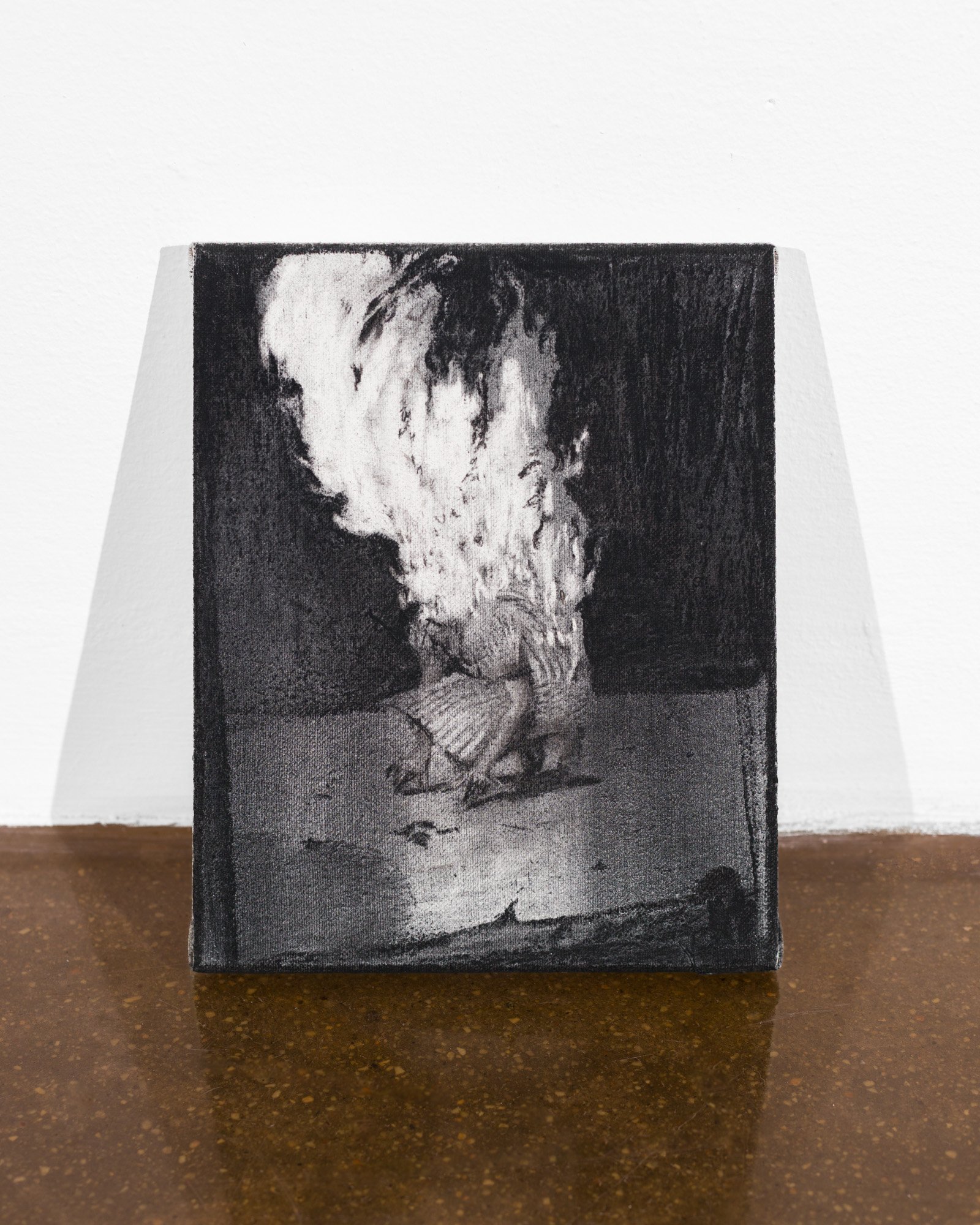

Death & Transcendence

These drawings don’t depict death as an end, but as a passage. Through flame, decay, and disappearance, the body dissolves into other states – light, noise, myth. Here, identity fades into abstraction, and the mortal becomes metaphysical.

Surreal Encounters & Pop Culture

Noir lighting, fetish shoes, romantic tropes, surreal objects – this group of drawings plays with familiar imagery while twisting it through irony and abstraction. Cultural icons become masks; clichés become symbols of something deeper, darker.

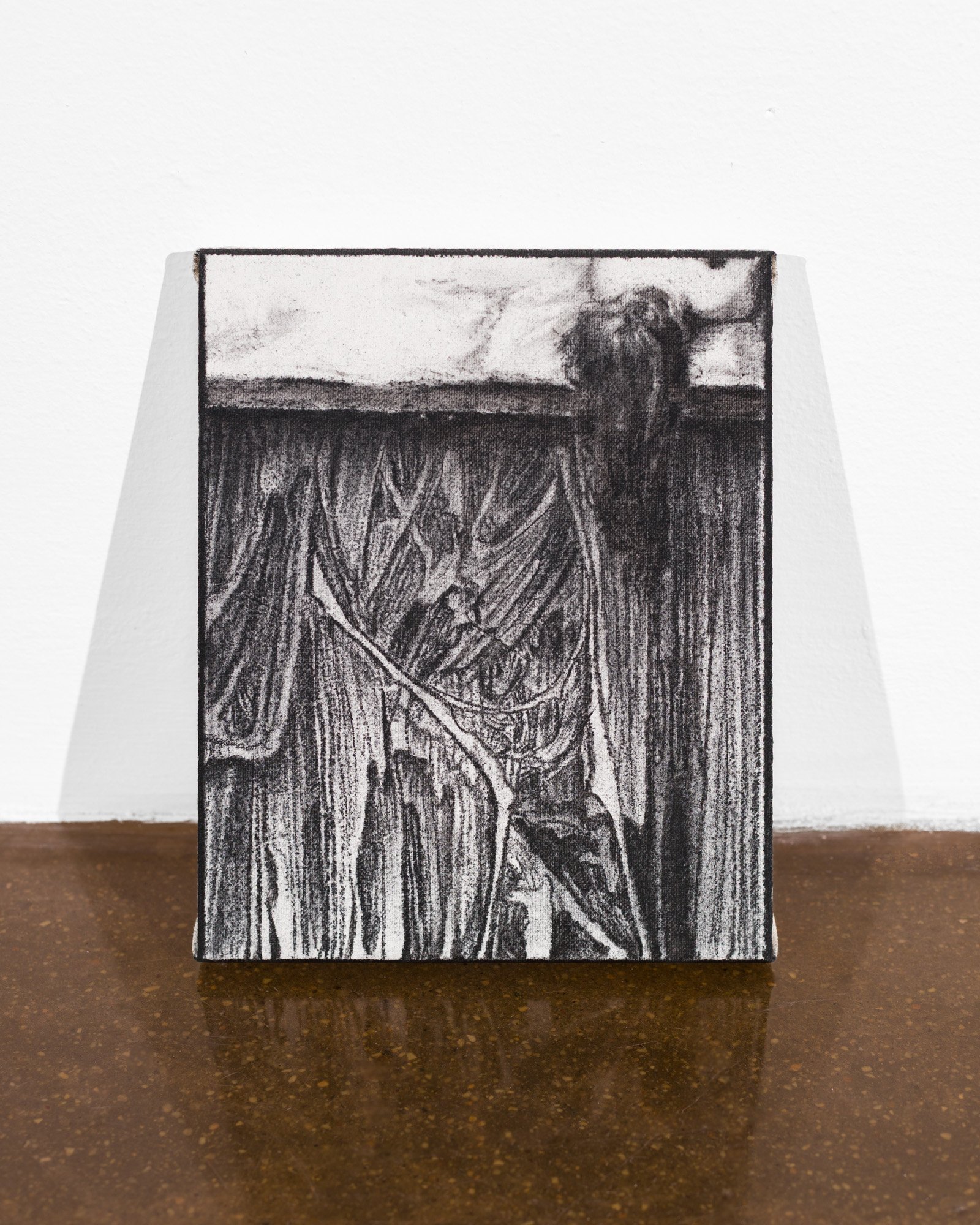

Echoes of the Occult

These drawings whisper rather than scream. Figures flicker like memories or rituals half-remembered. The ghosties, the witch tree, the hollowed-out body of Vamp — and the morbid kiss of Plague — all speak to a kind of spiritual residue. The occult here is not theatrical; it’s intimate, atmospheric. The paper breathes with silhouettes that feel less drawn than summoned. Illness, identity, and femininity blur into one continuous shadow.

Prologue: The Omen

This drawing came first—before the others, before the series took shape. A face, still and silent, lies beneath the carcass of a bird. A candle drips wax like blood. The scene is ritualistic, but also deeply personal—like a dream one cannot fully recall.

The piece takes its title from a sailor’s superstition: killing a seabird brings misfortune. But here, that misfortune feels almost welcomed—tenderly offered. This image marked the beginning. All twenty-one works that followed emerged from the atmosphere, intuition, and unease born here.